15 Minuten

Les “recettes” d’Éliane (Éliane's “recipes”)

Music that can only be created through continuity.

If there is an “incident,” repeat it two or three times to integrate it, but no more!

The new sound must come from far away; introduce it as if it were obvious, so that it is heard at first as a light veil.

Know how to create emptiness within density.

In each part, there is always something that remains from the previous one.

Stay relaxed and fluid.

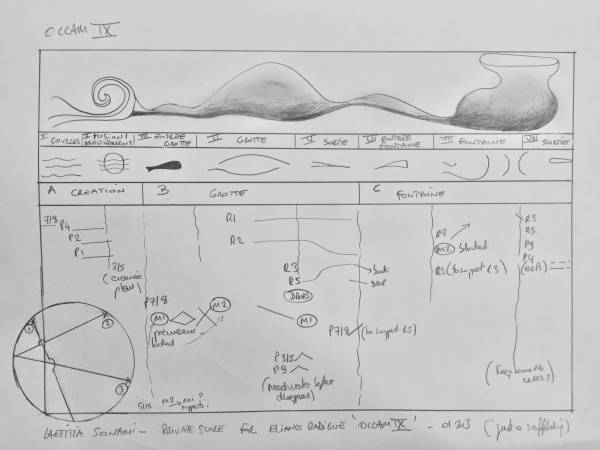

The theme (“the image”) is a working protocol, like plans for an architect or scaffolding for construction. It must disappear once the house is built.

Simplify! Simplify! Simplify!

The danger in this kind of working protocol: too much accumulation.

It's all in the balance. There must be no predominance. When something new emerges in something that is already established, you have to let it settle in, and then move on to another sound.

Everything evolves as a single thread.

Introduce, establish, live with it, free yourself from the anxiety of “structure,” don't accumulate (and don't stifle, either with too much bass or with perpetual movement).

Never try too hard to rebalance by going back.

You don't see a tree growing—you only notice the change once it's over.

When there is an “accident,” a sound that came too quickly, bring in another to help it disappear.

A sound is never alone.

Laetitia Sonami: I kept notes of the advice Éliane gave me when we worked on “Occam IX” in 2013. While some may be particular to this piece, most can be applied to all compositions.

It is a beautiful Occam, very personal. The deep, rich, and pure tones evolve in perfect harmony with everything that precedes them, without loss. Laetitia knows how to sustain the sounds she captures and brings forth from her hands. You can hear it, but it is even more spectacular when you see it. I am delighted that she has decided to share her instrument and her Occam.

Éliane Radigue, Paris, February 2024

Laetitia Sonami “a Song for two Mothers” (2023)

Recorded live at Roulette Intermedium, Brooklyn, NY, May 2023

Recording Engineers: Jonah Rosenberg and Eric Shekerjian

Mastering Engineer: Brendan Glasson

Spring Spyre, Max/MSP

While the original intention for “a Song for two Mothers” (aka: “Song of Tsar”) started as a sounding of silenced spaces, it became a crossing (une traversée) of concentric layers towards an anchored, moored space. These concentric layers are devoid of spatial or temporal directions — they are governed by a particular sonic behavior dictated by the training systems and models I have prepared in Wekinator1. For instance, the first layers use a catch-and-release patch I designed in Max/MSP, followed by a scanning of the Darbouka RAVE2 percussion model. Once exhausted, these systems are no longer used and the music moves towards a grounded space.

Éliane Radigue, “Occam IX” (2013–2023)

I still can remember where I asked Éliane Radigue to create an Occam for me: a small café on Rue Daguerre on a spring afternoon in 2012.

“What do you want to do?” Éliane asked me.

I did not know. I had left the lady’s glove behind, and I had a new instrument in the making, built to be more chaotic and improvisatory … not the ideal platform for a piece by Éliane.

“You will need to do exactly what I say. You are not going to like it,” she said.

That, I knew.

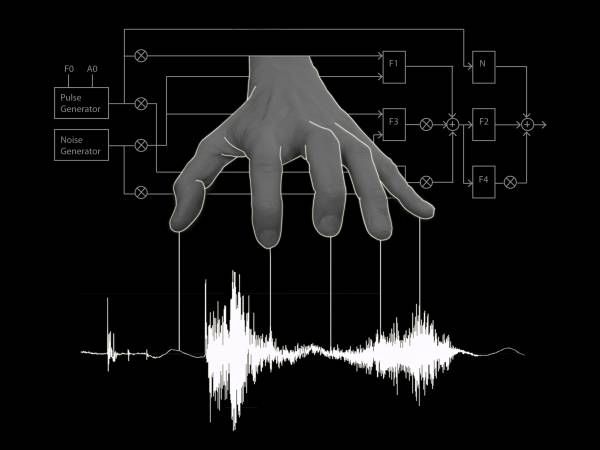

Hers was a music of slow transformation and perpetual flux — mine was of interruptions and contrasts. But thirty-six years after my first “class” with Éliane, I was finally ready to listen. I wanted to relinquish all control and desire and fully absorb how she was thinking about change, about sounds and the path they take. So began the process. My new instrument, the Spring Spyre, would need to be contained, its palette carefully prepared. Luckily, I had just been introduced to Miller Puckett’s phase aligned formant synthesis (Paf~), which had a rounder, smoother sound than the other synthesis I had previously used in Max/MSP.

Creating the palette was the easy part. I presented it to Éliane and she started conducting me on how to weave the sounds through a trajectory guided by a chosen image: the scaffolding, as she refers to it. Playing it, however, required meetings upon meetings, and much frustration because of my rushing, anticipating, not hearing, not being present, and not understanding the alchemy of fades and crossfades. I loved every second of it. I was entering Éliane’s world, trusting her and bending to her will. Each performance of “Occam IX” remains a learning experience.

Created in Dangu, Normandy, in 2012–13

Recorded live at Mills College Concert Hall, Oakland, CA, August 2023

Recording and mastering engineer: Brendan Glasson

Spring Spyre, Max/MSP

The Spring Spyre

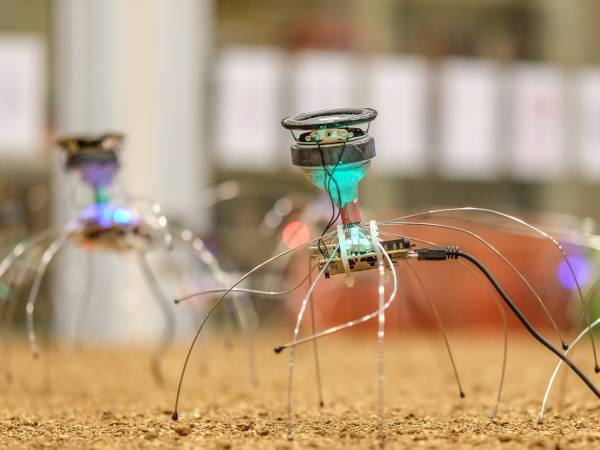

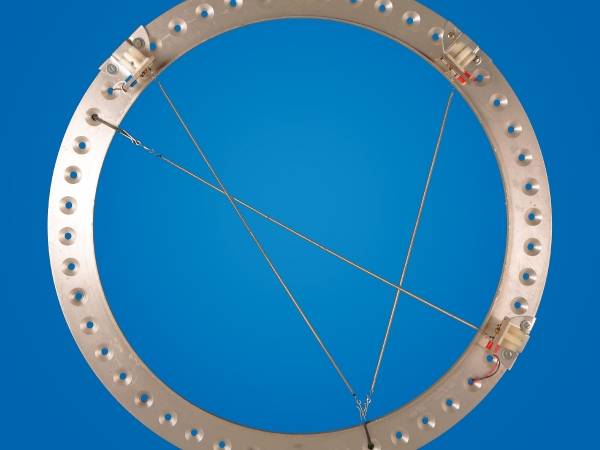

Both compositions on this LP were composed and performed with my instrument, the Spring Spyre. While “Occam IX” was the first composition for this instrument, “a Song for two Mothers” is the most current composition I have explored with it, ten years after it was built.

The Spring Spyre is composed of three thin springs that are attached to reverb tank pickups, mounted on a metal ring. The audio generated when the springs are touched, rubbed or struck is analyzed in Max/MSP. The extracted features are then used to train machine learning models in Wekinator and Rapidmax and control the audio synthesis in real time. We never actually hear the springs.

The trainings can be restrictive, as in “Occam IX”, allowing for predictable behaviors, or they can be vast and unruly, allowing for a catch-and-release procedure where the sounds can be “frozen” while on an unpredictable trajectory.

This instrument cannot be dissociated from the compositions: it is an integral part of the dance, pressing its personality onto my imagination.

Listen to the album at the Sounding Future AudioSpace

Info about the record:

This record is dedicated to the two Élianes.

Cover Photo by Patrick Sumner

Additional photos by Renetta Sitoy, Laetitia Sonami,

Marc Battier, Rebecca Fiebrink

Design by Lasse Marhaug

Liner notes by Laetitia Sonami, Paul DeMarinis, Éliane Radigue

Copy editing by Curran Faris

Mastered for vinyl by Joe Talia at Good Mixture

© 2024 Black Truffle records

Laetitia Sonami (BMI), Éliane Radigue (Sacem)

BT122

www.blacktrufflerecords.com

The first thing we hear is sound.

(It could not be silence, a thing so rare that we need to conceptualize it

and then hunt for it, or devise an approximation.)

The first thing we hear is sound. A sound.

But sound soon splits. Into two or many, revealing space.

Make room!

(It does not matter if one sound is noisy, the other piercing; or one low, the other right here.)

And then, only then, as to Condillac’s dumb but attentive statue, the cessation, repetition, or variation of sound gives rise to an awareness of time passing.

But time, the time of sound or the time of life, is illusory. (We know that innermost; we don’t need wise men to tell us). Even though we understand sounds and music to evolve in time, as we listen, time ultimately disappears. It is space that unfolds.

(The time of music is very simple indeed — once-upon-a-time, beginning, middle, end. That’s it. But the places we go!)

And space, yielding space, ever willing, ever open, generously creates places, dimensions, hidden folds and valleys, vast views and vistas for these sounds as they burst forth from that first marvelous horn of hearing, the cochlea.

Space appears infinitely capacious, and we might think it really so, were it not for its boundary — the end.

Perhaps we should fold that abstraction back into our bodies and consider the end as not something of time, but of exhaustion. Exhaustion sets in, the four platitudes reveal themselves.

Paul DeMarinis

First:

“Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem”

Occam IX

Éliane Radigue’s Occam series is perhaps the most singular body of work in the electroacoustic repertoire, for, with few exceptions, these pieces are performed without recourse to electronic devices at all. Rather, each Occam features sounding bodies in the form of classical musical instruments. Performers use extended techniques to evoke drifting harmonics, resonances and drones which have their aesthetic origins in Radigue’s analog electronic synthesizer works from the 1970s and 1980s. Now numbering over eighty instances, each Occam is composed for a particular instrumentalist or ensemble and remains their individual repertory asset. The performer may, given proper circumstances, pass the work on to another single performer.

Perhaps an Occam is a formal invention, like the sonata or concerto were in their time.

Or, perhaps, it is a social innovation, where a group of musician-acolytes are bound together by their individual Occams yet they never meet to perform them together. And then, there is the economic question: Is an Occam a license for a performer to improvise on their instrument and tie the provenance of the result back to the composer, then transfer it to a single other performer, like a liquor license?

At this point, recourse to etymology is tempting: the title “Occam” may be derived from William of Ockham, a 13th century philosopher-monk, perhaps by the way of the phrase “Occam’s Razor,” which stipulates that systems should only be as complicated as necessary, and no more; the razor would cut out the redundant features and the work would rest perfect and complete in it’s pared-down form. This may be what the composer had in mind. And yet, when we examine the many Occam pieces of Radigue we discover that they all have at their root the image and the feeling of water: upwelling, ceaselessly flowing from deep springs through rivers to the sea. Such images seem distant from the sensibility of Scholastic philosophers and are more in accord with the pre-Socratics, as with Heraclitus’ “panta rhei” — everything flows. And flow itself appears core to the musical energy at operation within the many Occams of Éliane Radigue.3 What could be cut out from a system of flow to simplify it? What power has a razor over water? Radigue and the performers agree that every Occam is an “image” transmitted from composer to performer “osmotically.”4 Again, a liquid metaphor.

Flow and Drift

The easiest thing for an oscillator to do is just to drone on a single pitch forever. As it does so, it becomes an increasingly perfect flow, laminar and smooth (i.e. self-similar) and will ultimately consume both the space and time of sound. Anything else requires intervention. Anyone who has some experience performing on analog synthesizers understands that they are, quintessentially, analog computers. Kith to the historical hydraulic computer that managed the national finances of Guatemala in the 1950s, synthesizers like the ARP 2500 regulated and modulated the flows of electrons, analogs to the flow of water. The currents surging within their circuits and along their patch cords operate in a frictionless world, beyond gravity, and in a sense, beyond time, certainly beyond concert time. As Bob Ashley said of the Moog, “[it] plays forever… until the power goes out.” Thankfully, within this timeless flow there is slippage. Amongst this is frequency drift, not of the harmonic from the fundamental of a given oscillator, but among the various oscillators simultaneously flowing.

There is a curious phenomenon deep within our listening brains to perceive as a spectral unity any group of harmonically related frequencies that are synchronized over a perceptual moment of time. They seem to coalesce into a single sound, sometimes called a “waveform” (although that term forms a false cognate with visual representations). If one creates separately each overtone of a given static timbre and sums them together, absent any phase drift, they will form, without any coercion, a unity. Letting the partials drift slowly will break the illusion. Similarly, the harmonics of one spectrally rich oscillator drifting with respect to those of another will produce the shimmering effects achieved in Radigue’s earlier electronic works for the ARP 2500. This sonic quality is replicated in the Occams by the intrinsic sounds of the instruments: “For me true harmonics are the ones that appear by themselves, not those that are actually played on the instruments, the latter end up becoming new fundamentals.”5 That is, the relation of the harmonics to the fundamental in the musical instruments are not fixed as they were in the waveforms of the ARP 2500, but inherently possess flow and drift from the acoustic complexities of the vibrating physical bodies.

Laetita Sonami’s “Occam IX” is one of a very few Occams that is realized using electronics and perhaps the only one whose realization is accomplished with fundamentally digital means. Sonami uses a host of Paf~ oscillators operating in a Max/MSP environment as her sound source, both for “Occam IX” and for “a Song for two Mothers.” These are modulated by the Spring Spyre: not an instrument in the classical sense, nor a “controller” or even an “interface” as they are defined by HCI. All Sonami can do is to touch the Spyre’s languidly coiled springs, giving rise to small flows of electromagnetic eddy currents, which, digitized, enter into an opaque digital neural network that gives rise to numerical sequences within the computer. These in turn are routed and gated to give rise to yet more streams of data, which, by no means exhausted, are directed to the DACs, thence to amplifiers and loudspeakers that generate a faint breeze to the ears. Listening, feedback, flow — all of these come after the fact. In a sense, opacity and exhaustion serve as stand-ins for flow and drift. Yet, like the acoustic Occams of strings or wind or wood or catgut, Sonami’s “Occam IX” of computer code is nonetheless a flow of the ARP. Considered in that way, number IX is perhaps Occam’s worst nightmare — in complicating the reducible, it betrays digitality at its root.

Second

Mephistopheles: “These heathen people are none of my business;

They dwell in their own hell;

But there is a remedy.”

Faust: “Speak, and without delay!”

Mephistopheles: “I hate to discover a higher secret;

Goddesses are enthroned in solitude,

around them no place, still less a time;

to speak of them is an embarrassment.

The mothers they are…”

Faust: “The mothers! Mothers!

It sounds so strange!”6

“...around them no place, still less a time;” — how better to express the paradox of digital sound?

The layered depths and gradual upwellings reminiscent of the flow of water are nowhere present in Sonami’s “a Song for two Mothers”; rather, there seem to be a slow parade (carnaval?) of overlapping screens, staged sonic events, a series of tableaux vivants. We are surrounded, yet nowhere. Metallic birds twitter in trees, awaiting the advent of a presence who will not manifest. We pass through as itinerant observers, unnoticed as we listen, evident only to ourselves.

In her article “Seizing a Sound and Smelling its Belly to Fit in a Folder”7, Sonami has suggested that sounds might be categorized by their apparent distances. Most significant in this organizational method is that her metric of distance is not only compounded of parametric (loudness, pitch) and perceptual (reverb, signal-to-noise ratio) qualities, but also of psychological dimensions of a more complex type. Here it is important to qualify that Sonami was speaking primarily of sampled sounds, that is, specific segments of recorded sounds that are excised from their matrix to be combined compositionally by playback, repetition, time-modulation, signal processing or mixing, a process that underlay much of her work at the time. She highlights relational features such as “the sound of a dog panting is close, the time it takes to understand IT IS a dog is very fast, hence a short distance.” Similarly, “voices on a PA system” represent authority and thus are more distant because “you are never addressed singularly, you can extract yourself.” All these qualities infer a diegetic relationship of sound to source.

Unlike Sonami’s earlier work combining live voice, audio samples and digital controls and signals, “a Song for two Mothers” is a purely digitally generated sound work. Thus, there are no diegetically implicit distances among sounds as she outlines in her essay. Without distance how might we prise apart these sounds, or even swallow them whole?

If digital sounds may be said to manifest foreground or background properties (or ur-ground, for that matter) then it is in an endless and often swift exchange of energy between sample and glitch (where, by “sample” I mean an intended sound with specifiable and audible properties, and by “glitch” I mean all the transients and sidebands that exist as “extra-men” and whose sonic properties are modulated [relegated to a subordinate realm] by psychoacoustic happenstance).

And yet, as with all sound, there is space, but here defined more by sequential limits, something like the frame of a painting or the horizon line of a frieze. As long as the sounds appear shorter than the perceptual frame, they are close by and interact in that realm. But when they become longer, dronelike, we have a tendency to internalize them, like a mental state; or, rather, we enter them as a moving train: the sound becomes a vehicle to transport us through space.

And so it is in “a Song for two Mothers.” A series of scenes develop out of chirpings and impulses. Nothing to hold on to here. But then, at eleven minutes, the slow fade-in begins, as two tones try to coalesce, each striving to hide within the other — what a clever turn it will be if they can manage it; a foggy wailing tone emerges and we are now in a place of continuity very different from the analog flow of “Occam IX.” Transport. Coming and going, going and returning. As though turning us over in its mind, the slow pulsing siren considers, passes, absorbs or expunges the initial eleven minutes of the piece. No matter how long it takes, we are inexorably headed to its destination.

All this space is movement from one place to another. Flowing water, or a parade? Neither. Perhaps the mothers are reciting a lesson for us. And, in the end, it’s about how to change, to be still and to keep moving.

Third

Multiple Mothers

That the two works on this album, so different in character, so different in nature, could be realized with almost identical means — Max/MSP, the Paf~ object, the Spring Spyre — is, I think, less a testimonial to the avowed universality of digital synthesis than it is to the duality of mothers mentioned in Sonami’s title. The substance of sound is as much resonance as it is vibration. If the first is somehow within us, the second is discovered as we make our way through the world.

Fourth (Explanation)

The miracle of language is that one word can mean so many different things;

And then, that there are so many different words for the same thing;

Words and things; nickels and dimes.

The binding energy that holds words together in a text, against all odds: meaning

When that force absconds, words fly off their separate ways.

Sounds, like words, have individual existences; thus form, volume and shape.

But the physics of sound is different.

Sounds may fly off, or merge, hiding in one another.

Here the two are held in one,

and that one, with another

Two converging spirals,

one matrix, two mothers.

Paul DeMarinis

Good Friday, 2024

The Giga-Hertz Lifetime Achievement Award honors artists whose visionary work has profoundly shaped electronic music. This year’s award goes to Laetitia Sonami, whose pioneering practice since the late 1980s has expanded the boundaries of sound, performance, and technology. Visit our AudioSpace ZKM colllection for more info and music.

- 1

http://www.wekinator.org/

- 2

RAVE: Realtime Audio Variational autoEncoder.

https://github.com/acids-ircam/RAVE?tab=readme-ov-file - 3

“Citing the ocean as a calming antidote to the overwhelming nature of our vibratory wave-filled surroundings, Radigue has named the tributary components of her Occam series with the image of fluid water in mind. Solo pieces are Occams, duo pieces Rivers, and larger ensemble pieces Deltas. “

“Pace Gallery Press Release, Éliane Radigue, Occam Ocean”, Blank Forms, Accessed March 29, 2024, https://www.blankforms.org/events/eliane-radigue-occam-ocean#:~:text=Citing%20the%20ocean%20as%20a,and%20larger%20ensemble%20pieces%20Deltas. - 4

Éliane Radigue. Occam Ocean 2, Shiin, 2029, EER2, compact disc. Liner notes pg. 47.

- 5

Éliane Radigue. Occam Ocean 4, Shiin, 2029, EER2, compact disc. Liner notes pg. 49.

- 6

J.W. von Goethe. Faust part II, translated by Torsten Schwanke, Scribd, accessed March 29, 2024, https://www.scribd.com/document/676052411/Goethe-the-Mothers.

- 7

Laetitia Sonami. “Seizing a Sound and Smelling its Belly to Fit in a Folder” in Arcana III: musicians on music, ed. by John Zorn (New York: Hips Road), 2008.

Laetitia Sonami

Laetitia Sonami is a pioneering French sound artist and performer whose work has redefined the relationship between body, technology, and sound. After studying with Éliane Radigue in France, she moved to the United States in 1977 to pursue electronic music at SUNY-Albany and the Center for Contemporary Music at Mills College. Her performances, live film collaborations, and sound installations explore presence, participation, and the intimacy of sound, transforming places and objects into poetic interfaces of perception. A pioneer in wearable technologies, Sonami designed gestural controllers that turned movement into sound. Her iconic “lady’s glove” (1991)—an elegant, sensor-laden interface—became her primary instrument for 25 years and inspired a generation of artists to rethink the body’s role in electronic performance. Continuing her exploration of embodied interfaces, she developed the “Spring Spyre” (2013), integrating machine learning into real-time sound synthesis, and more recently the minimalist “lady’s ball(s)”.

Eliane Radigue started her electronic music career in the 1950s. A student of Pierre Schaeffer, she later became assistant to Pierre Henry. Eliane first started exploring pieces using feedback techniques and later adopted the ARP 2500 modular system which she used as her instrument for more than 30 years. In 2000 she created her last piece for the APR and tape, L’Ile Re-Sonante, for which she received the Ars Electronica Golden Nica. Since 2001 she has composed mostly for acoustic instruments. Major works include Geerliande, Adnos, Jestun Mila, Trilogie de la Mort, Naldjorlak and the more recent OCCAM series. Recent publications exploring the life and work of Eliane Radigue: “Eliane Radigue - Intermediaty Spaces, Espaces Intermédiaires” Julia Eckhardt (Umland Editions), “Entretiens avec Eliane Radigue” Bernard Girard (Editions Aedam Musicae), and “Eliane Radigue – Portraits Polychromes” (Institut National de l’audiovisuel)

Paul DeMarinis has been working as an electronic media artist since 1971 and has created numerous performance works, sound and computer installations and interactive electronic inventions. One of the first artists to use computers in performance, he has performed worldwide. Much of his recent work deals with the areas of overlap between human communication and technology. Major installations include "The Edison Effect" which uses optics and computers to make new sounds by scanning ancient phonograph records with lasers, "Gray Matter" which uses the interaction of flesh and electricity to make music, "The Messenger" that examines the myths of electricity in communication and recent works such as "RainDance" and "Firebirds" that use fire and water to create the sounds of music and language. Public artworks include large scale interactive installations at Park Tower Hall in Tokyo, at the Olympics in Atlanta and at Expo in Lisbon and an interactive audio environment at the Ft. Lauderdale International Airport. He has been an Artist-in-Residence at The Exploratorium and at Xerox PARC and is currently a Professor of Art at Stanford University in California.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Laetitia Sonami

Laetitia Sonami

Laetitia Sonami  Éliane Radigue

Éliane Radigue  Paul DeMarinis

Paul DeMarinis