9 Minuten

Spatial sound reality — access is still the exception

No sugarcoating: for most artists, access to spatial sound is quite limited. You don't own an immersive sound studio or a beamformer. Instead, you apply for a grant or a residency, and if you’re lucky, you get a few days with a system — just enough to get lost in the manual and maybe try out an idea or two. Every instrument is a new learning curve, and by the time you start to get comfortable, your slot is up and you’re back to headphones and stereo mixes, or at best vague approximations.

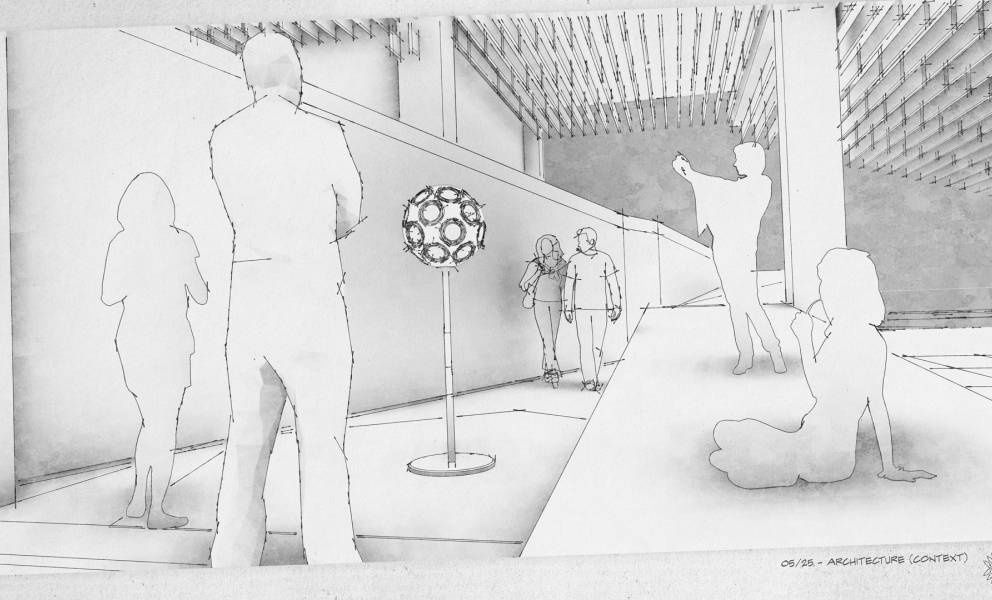

Institutions face a different but related challenge. You might have a dome or a multi-channel array, but these are often tied to a single space and require significant investment. This limits how many artists you can host, and what kinds of projects are possible. What if you could add a spatial sound instrument that doesn’t need its dedicated, permanent, acoustically treated studio, that’s easy to move, and that lets you take projects out into the world — into galleries, public spaces, or wherever people actually are? That’s the gap we’re hoping to fill.

Meanwhile, the traditional paths for composers and musicians have only gotten tougher. Each year, thousands of students graduate from music programs in Germany — industry estimates often cite figures upwards of 8,000 — while the number of full-time orchestral vacancies remains in the low hundreds or fewer. This gap is widely discussed in music education circles and reported by professional associations, though precise annual figures are not always published.

Entertainment and pop music world is no different - everyone's eyes are on stars like Taylor Swift, or self-made revelations like Jacob Collier, promising a vibrant career within reach. But for 99% of artists the reality is harsh — with over 60,000 new tracks that are uploaded to Spotify every day, most artists see mere pennies per play and struggle to launch their careers. If the old “stereo” world is dying, why is it still so crowded? Inertia is one thing, lack of access to tools that could set you apart — like spatial sound — used to be the other.

But this is changing, and new interesting careers in sound are opening for those willing to take a step away from the beaten path.

Why I got obsessed (and why you might, too)

My journey into spatial sound began with curiosity and a sense of possibility. For two decades, I worked at the intersection of technology, art, and space — mostly on the visual side. But after reaching many of my goals there, and anticipating the tectonic shifts sweeping through the industry, I made a conscious, deliberate decision to leave the now-colonized world of visuals and venture into the less-explored territory of spatial sound.

In filmmaking, we often say that "Sound is 50% of the experience" — I used to take it with no grain of salt. But perhaps it isn't?

Today, I am convinced it's more. Every time I encountered a truly immersive experience — like the 4D Sound system at Monom in Berlin, or Gerriet Sharma’s work with beamforming arrays at Spaes — I left wanting more. Not just as a listener, but as a maker.

What struck me most wasn’t just the technology, but how these systems could make you feel like you were listening to space and sound itself, not just to speakers.

Yet, these experiences used to be rare, locked away in specialized studios and research labs, accessible only for the luckiest or most determined few. I wanted to change that. (If you’re curious about the deeper story and the ideas that shaped this project, I wrote more in The Futures of Sound.)

The Lighthouse of Sound - ambisonic arrays turned inside out

Let’s talk about the instrument itself, and why it’s different. Traditional ambisonic domes or surround sound systems work by surrounding the listener with speakers, projecting sound inward. It’s a bit like sitting in the center of a planetarium — if you’re in the “sweet spot,” you get a somewhat convincing sense of spatiality. But step outside that zone, and it’s just a bunch of speakers.

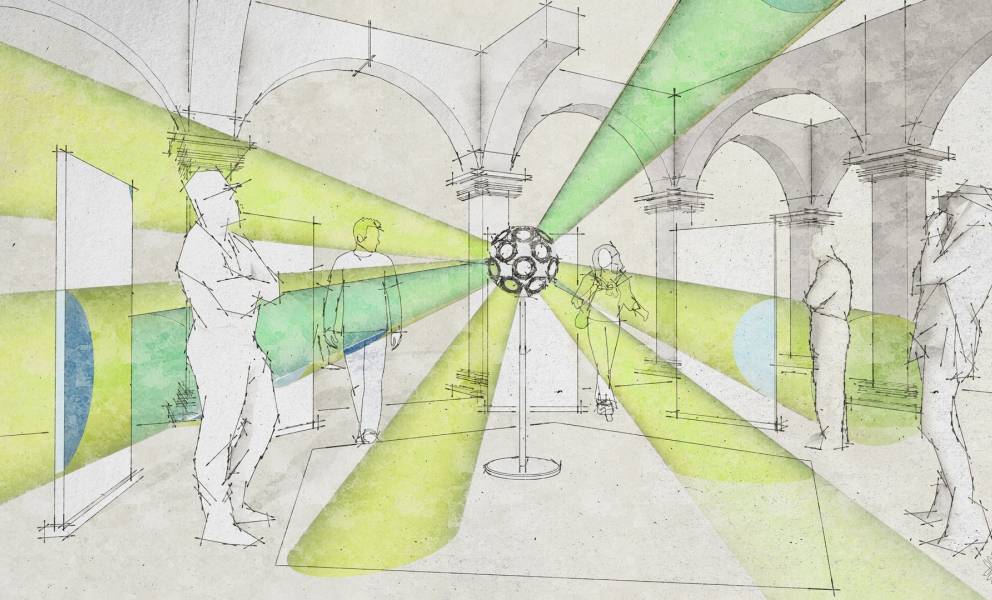

Spherical beamforming arrays — what we’re building — flip this idea inside out. Imagine a lighthouse, but instead of casting light, it projects beams of sound outwards into the room. These beams bounce off walls, ceilings, and bodies, filling the space in unpredictable, lively ways. You don’t need a perfectly treated studio. In fact, reverberant spaces — churches, small halls, even industrial sites — become collaborators rather than obstacles.

This isn’t about isolating the listener in a pristine bubble of idealized “reference sound”. Rather, it’s about social listening: bringing people together, letting them move around, and inviting the architecture itself to shape the experience. The spherical, “totemic” design isn’t just practical — it’s symbolic. It organizes space, draws people in, and offers a focal point for shared exploration.

"Spherical beamforming what…?"

Let’s break it down. For me, this project started as the Quest for the Holy Grail — building a holosonic projector, something that could precisely project beams of sound across the full frequency range and allow us to explore sound as space and in relation with architecture. That’s beamforming — the pinnacle of spatial sound control, pioneered by IEM over many years of research.

This story starts many years ago in the circles of IRCAM as a vision to reproduce sound radiation characteristics of real instruments. But probably it was too early — despite the ambition, the tech was not there. The project would probably never see the light, if not for the attention and years of development led later by Franz Zotter and the team at IEM. Not only Franz laid out all the hard-core theory between maths, physics and acoustics, but pioneered the ground with the first IKO prototypes around 2006, later developing it within the OSIL project and concluding in Sonible's IKO around 2018.

Singing Watermelons would not be possible without these cornerstones. And this would have been much tougher a challenge without more then generous personal support from Franz Zotter, Stefan Riedel and great minds in the circle.

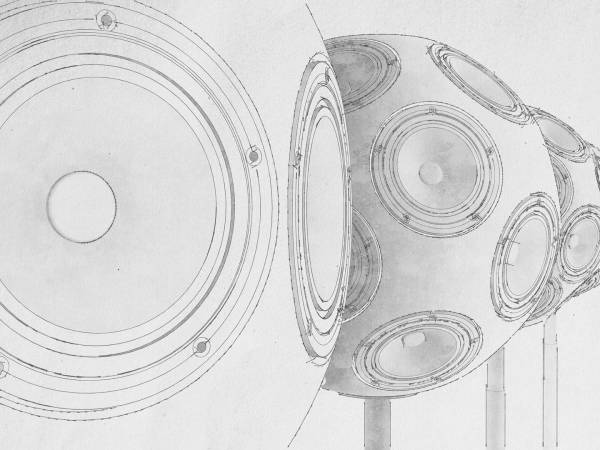

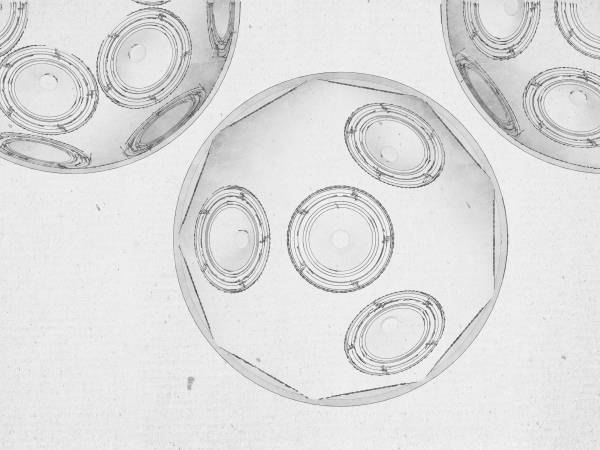

With foundations in place, my main goal has been taking it further, helping spread this approach beyond the academic circles — making more accessible to artists and practitioners. This prompted strong focus on the design, and spherical form factor. IKO has the layout of icosahedron - a platonic solid with 20 triangular sides. That's beautiful, but limiting. A spherical form factor allows for a variety of speaker layouts, and that's exactly what we've been focused on, with a family of designs from 16 to 24 drivers.

Beamforming aside, as the project progressed I spoke with spatial sound practitioners around the world and realized

Slovox Svarog24 Spherical Spatial Sound Speaker, July 2024

So what is it? It’s a bunch of speakers in a compact enclosure, if you like. You can feed them a single signal, if you want. But that’s boring.

It’s a bunch of speakers — and each one can be individually controlled. Use it as a multi-channel instrument. Take advantage of intuitive workflows you already know in your DAW, with Max, or Supercollider. At this stage, it’s already opening up a vast range of possibilities in electroacoustic, acousmatic, or just electronic composition. Use it in live acts, installations, or theatre. I keep getting surprised.

But we can do much more — this “bunch of speakers” can be treated as a precise sound radiator, used to decode and diffuse higher-order ambisonic signals, for those who work in or believe in that format.

And as you move towards more sophisticated usage, this “bunch of speakers”, combined with beamforming workflows, becomes an ultra-precise holosonic projector — a lighthouse of sound, animating evolving sonic sculptures that are interwoven with the architecture and surroundings.

Here, the room — with all its acoustic imperfections — is not an enemy anymore. Instead, it becomes a collaborator, inviting a much more organic and creative approach than what years of Hi-Fi marketing have conditioned us to chase: the myth of "pristine, reference sound". Isn’t that, in itself, an elegant answer to the endless debate between the prohibiting “sound engineer’s ears” and creativity-seeking “artist’s ears”?

Lastly, beamforming (and higher-order ambisonics), when paired with a central spherical loudspeaker, remain the Wild West of sound exploration — only a few dozen compositions have ever been created for systems like this. And that’s exactly what makes it so exciting.

For Institutions: more artists, more places

For institutions, adding a spherical spatial sound instrument to your toolkit doesn’t mean tearing down walls or building a new studio. It’s a way to complement what you already have — hosting more residencies, inviting more artists, and even taking projects out of the building and into the world. Imagine a residency where the instrument goes with the artist, or a festival where spatial sound compositions pop up in unexpected places.

The Singing Watermelons (and Their Friends)

At Slovox, the cornerstone project is the Singing Watermelons: a family of spherical multi-channel loudspeakers, each designed for versatility, affordability and portability. They fit in a couple of rack cases, and can be set up by a small team in minutes. Each instrument can project sound in multiple ways — omnidirectional, multi-channel, ambisonic, or as a beamformer — letting you experiment with how sound interacts with space.

One of the key challenges was coming up with ways of controlling these speakers. Each channel being controlled separately, requires a full chain: from an interface with sufficient number of channels, through digital-to-analog conversion (sometimes in the interface), all the way to amplification, all while staying on budget. While there already exist high-end solutions on the market that could satisfy all that, we wanted to achieve it at a fraction of price, using off-the shelf solutions. That's the essence of our Juiceboxes — a custom amp rack with all you need to to get these things working, and without breaking the bank.

Why Now? Welcoming Early Abandoners

After a sprint-marathon of R&D — learning from the research at IEM in Graz (and getting their generous and friendly support!), building prototypes, and testing — we’re getting ready to open things up. As of this summer, we’re inviting early abandoners (of the old world) and early adopters: artists, institutions, and anyone curious about what’s possible when spatial sound becomes personal and portable.

If you’re tired of waiting for access, or want to offer new kinds of residencies, workshops, or public projects, let’s talk. We’re not trying to replace domes or compete with the big labs; we’re building on their work, and hoping to make spatial sound a tool for more people, in more places.

Slovox

Slovox is an R&D lab dedicated to designing and building spatial sound instruments, systems, and installations. By making advanced spatial audio technology accessible to artists, researchers, and institutions, Slovox empowers creative exploration and collaboration — enabling new forms of social listening and sonic experience.

The Last Ear

The Last Ear is a platform committed to restoring the art of listening in an age of engineered distraction. Home to Slovox and the Echotronica festival, it unites art, technology, and radical attention to foster connection, creative resistance, and a community dedicated to advancing the art and science of listening.

Patrick Kizny

Patrick Kizny is a creative entrepreneur, artist, and recently — the founder of Slovox, known for his work at the crossroads of art, technology, and design. With over two decades of experience leading innovative projects in film, visual effects, and creative technology, he now focuses on pioneering new musical ventures and spatial sound instruments that challenge conventions and invite new ways of listening.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Patrick Kizny

Patrick Kizny

Patrick Kizny