30 Minuten

Here Comes Everybody. The light has turned. Walk on. The water is fine. Jump in. (Cage 1961, 134)

In this quote from his landmark book Silence, John Cage anticipated the diffusion and democratization of musical creativity that characterizes the twenty-first century. However, the superabundance of music driven by new technologies and today’s hyperconnected world have created a “content tsunami” that frequently overwhelms our cognitive abilities, creating a massive attention deficit (Bhatt 2019). In 1988, Cage used the phrase, “an anarchic society of sounds” (1990a) to describe the process he was using to compose his late works. While it originated in a totally different context, the term seems to accurately describe the highly chaotic, diffused state of current global musical culture. In a 1968 essay dedicated to Cage, his biographer Richard Kostelanetz coined the term “technoanarchism” to describe how, “by freeing more people from the necessity of productivity, automation increasingly permits everyone his artistic or craftsmanly pursuits” (Kostelanetz and Puchowski 1999, 259). This prediction has become a reality in today’s world, in which nearly a million songs are released weekly on Spotify, and 500 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute (Ceci 2023). Soundcloud is an online music service that allows its users to upload material without going through a distributor, similar to YouTube. The platform currently hosts 250 million tracks (Soundcloud 2023), more than double the number available on Spotify (Spotify 2023). Users of the AI music site Udio are creating ten songs per second, or 864,000 every day. The technoanarchism that characterizes the landscape of music today strongly resonates with Attali’s ideas, which predicted that everyone would become a composer. “Music is no longer made to be represented or stockpiled, but for participation in collective play, in an ongoing quest for new, immediate communication, without ritual and always unstable” (1985, 141).

The macroscopic view of music today as anarchic is mirrored in the technical aspects of musical structure. Google’s Magenta Studio is a series of applications that use machine learning and AI to enable users to create original music instantly. Herremans et al. have pointed out the significance of the Magenta project, stating that it exemplifies how “music generation systems will become ever more prominent in our day-to-day lives” (2018, 25). Attali has also updated his predictions regarding the ubiquitousness of composition to include AI technologies (Clancy 2023). All of the Magenta applications include a slider labeled “Temperature,” which is essentially a randomness control. According to the description on the Magenta Studio website, “higher values produce more variation and sometimes even chaos, while lower values are more conservative in their predictions” (Magenta Studio). Experiments with Temperature control inside of the Generate app, which produces melodies, demonstrate the software’s ability to create infinite variations based on the degree of chance or randomness introduced into the neural network. The ease of use makes the process of generating music incorporating random and chance elements accessible for anyone. Randomization of elements is a standard feature in mainstream computer music applications today, and many apps such as Melody Sauce, Riffer, and Melodya are strictly dedicated to generating melodies through random procedures.

The introduction of randomness into the process of musical creativity was fundamental to the trajectories of externalization and democratization. Lejaren Hiller, the first composer to create music using a computer in the late 1950s, described music in terms of information theory as, “lying somewhere between complete randomness and complete redundancy” (1959, 110). He carried out pioneering research on algorithmic compositional techniques, which form the basis for the Magenta Studio and other similar applications. While algorithms today are thought of as being specifically associated with computing, the term is not limited to that context. The incorporation of algorithmic processes in music extends back as far as the Renaissance (Collins 2018; Muscutt and Cope 2007). The use of algorithms is a primary vehicle for the externalization of musical creation and has a strong connection with the concept of autopoiesis.

The term algorithm was first associated with the ninth-century Persian mathematician Abu ‘Abdullah Muhammad ibn Musa of Khuwarizm. The late Medieval Latin stem of the word, algorismus, is an adaptation of his name, al-Khuwarizm, and was defined at that time to mean the decimal number system of arithmetic that is still the meaning of modern English algorism. The term algorithmus appeared in an early German mathematical dictionary, Vollstandiges Mathematisches Lexicon (1747), and was originally used as a general term for arithmetic (Burns 1994). The word’s form changed to algorithme in seventeenthcentury France, and the meaning remained the same until the modern notion of algorithm emerged in English in the first half of the nineteenth century. In 1843, British mathematician Ada Lovelace, the daughter of poet Lord Byron, wrote what is now considered to be the first computer algorithm in history for Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine. Babbage had created a mechanical calculator that he called the Difference Engine in 1822, and the Analytical Engine was intended to be a programmable computer that would succeed the first device. While the Analytical Engine was never built, Lovelace saw its potential for broader applications beyond number-crunching, including the creation of music.

Writing in the notes to an article on Babbage’s Analytical Engine for which she was the translator, Lovelace described the potential of this new technology:

Again, it might act upon other things besides number, were objects found whose mutual fundamental relations could be expressed by those of the abstract science of operations, and which should be also susceptible of adaptations to the action of the operating notation and mechanism of the engine . . . Supposing for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent. (Menabrea 1843, 694)

Although she remained practically forgotten for more than a century, this pioneer initiated a long journey that has continued to the present proliferation of AI. The term became more commonly used in the mid-twentieth century, triggered by the emergence of computer technologies (Kowalkiewicz 2019).

The Oxford dictionary lists three definitions of algorithm. The first is synonymous with the previously mentioned algorism, while the mathematical definition is, “a process, or set of rules, usually one expressed in algebraic notation, now used especially in computing, machine translation and linguistics” (2012). Burns points out that the third definition, taken from medicine, has the closest association with musical applications of the term (1994); “a step-by-step procedure for reaching a clinical decision or diagnosis, often set out in the form of a flow chart, in which the answer to each question determines the next question to be asked” (Oxford 2012). With the advent of information theory and computers, the use of algorithms to create music became more widespread and understood. However, chance and random procedures as implemented by early twentieth-century composers bear a strong conceptual connection with algorithmic concepts (Burns 1994).

Serialism and Autopoiesis

At the same time that Duchamp and the Futurists were creating new models of music through the use of chance, noise, and improvisation, Arnold Schoenberg and others in the Second Viennese School were composing atonal works that aimed to transform the art of composition through different autopoietic and algorithmic methodologies. Schoenberg’s prolific writings and music influenced numerous younger composers, most notably Alban Berg and Anton von Webern, who joined the effort to radically alter music composition as it had been known previously. From 1908 to 1914 these composers created music in a freely atonal style that consciously avoided diatonic harmony and repetition in their effort to create an entirely new musical language. In the early 1920s, Schoenberg developed his “method of composing with twelve tones which are related only with one another,” (1975, 52), in which the twelve pitches of the octave are regarded as equal, and no one note or tonality is given the emphasis over any other. Numerous writers have described Schoenberg’s methodology as a “democracy of notes,” a leveling of the hierarchies of tonality (Bennett 2009; Dienes and Longuet-Higgins 2004; Slonimsky 1933).

While the idea was limited to the embodied structure of musical composition as defined by Leonard Meyer (1967), the fundamental concept can be seen as foreshadowing broader examples of musical democratization. Schoenberg’s system asserted an intellectual and rational approach to creating music that challenged the excessive expressivity of late romanticism, replacing that idea with an algorithmic, rule-based structure that automated composition (Kaletha and Kohl 2004). Schoenberg’s vision is another manifestation of the externalization of musical creativity, and informed generations of younger composers who extended and expanded his ideas to other aspects of music including rhythm, duration, and large-scale form. This thread of composition, known as total serialism, reached its apex in the 1950s and 1960s with the work of Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Milton Babbitt.

Mário Vieira de Carvalho has pointed out that the serial music of the early 1950s is a great example of autopoiesis. In the self-referential and closed structures of works by Stockhausen, Boulez, and Goeyvaerts, the role of the composer becomes that of a “mere ‘observer’ or ‘accomplisher’ of the generating serial principles on which the work was based” (2001, 33). The different series of pitch, rhythm, and dynamics, are likened to the genetic material of the composition which emerges from the interaction of elements in the system. This externalization and objectification of the compositional process influenced generations of composers, and presaged current algorithmic music generation software. However, it was one of Schoenberg’s dedicated students who would pioneer an even more radical implementation of the idea of autopoiesis in music and shake the very foundations of the art form.

John Cage and Musical Anarchy

Many critics, artists, and writers have described John Cage as the single most influential figure in art, poetry, and aesthetics of the second half of the twentieth century. Cage challenged the most basic foundations of music and art, opening them up into an “emancipatory endgame” (Kahn 1997, 558).

RK: What would you say is your most important legacy to future generations?

JC: Having shown the practicality of making works of art non intentionally.

George Leonard argued that Cage fully realized the goal of Duchamp’s artistic project, bringing Western society to Wordsworth’s “blissful hour” when the art object can be dispensed with and we may emerge “into the light of things” (1994):

I’m out to blur the distinctions between art and life, as I think Duchamp was. And between teacher and student. And between performer and audience, etcetera. (Kostelanetz 1991, 23)

In his 2005 book Virtual Music, William Duckworth has noted:

More than that of any other composer, it is Cage’s music from the 1950s forward that sets both the stage and the tone for this nonhierarchic form of creativity. Rather than defining the composer-performer relationship in increasingly minute detail—as was the custom for the past thousand years—Cage created music that, through the use of chance operations, offered an ever-changing field of possibilities, and insisted that the performer, and often the audience, too, join in the creative act, thus blurring the boundaries not only of the process of composition, but also of the methods of its realization and final perception. (2005, 160)

Dieter Daniels writes that Cage allows the audience “to essentially self-determine its experiences with the artwork” (2008, 28).

Cage’s long and close association with Duchamp began when they met at a party given by Max Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim in 1942 (Mackrell 2013). Duchamp then asked Cage to write music for his part in Hans Richter’s film Dreams that Money Can Buy (1946), and while Cage greatly respected Duchamp, he kept his distance “out of admiration” (Tomkins 1998, 411). Duchamp had famously backed away from the art world in the 1920s to focus on playing chess, studying, and competing in numerous international tournaments. According to international master Edward Lasker, Duchamp was a “very strong player” and a “marvelous opponent” who would have ranked among the top twenty-five players in the United States during the 1920s and 1930s (Tomkins, 289). In the early 1960s Cage asked Duchamp for chess lessons, which Cage described as “a pretext to being with him” (Kostelanetz 1991, 11).

“Anything he did,” Cage wrote, “was of the utmost importance” (Lotringer 2000). The fascination with chess by both artists demonstrates their interest in systematic structures as well as subjects outside of the arts; Cage’s longtime obsession with mushrooms is comparable to Duchamp’s passion for chess. In 1968 chess was the focus of a performance event organized by Cage titled Reunion in which he and Duchamp played a game of chess with a chess board that was equipped with photoresistors and contact microphones (Cross 1999). The performance drew a crowd of several hundred people to the Ryerson Theater in Toronto. It will be discussed further in the next chapter.

In his book A Year From Monday Cage included a section called “26 Statements Re Duchamp,” in which he stated, “Had Marcel Duchamp not lived, it would have been necessary for someone exactly like him to live, to bring about, that is, the world as we begin to know and experience it” (Cage 1967, 70). In 1988, four years before he died, Cage conceived of an opera that would be called Nohopera, which he subtitled The Complete Musical Works of Marcel Duchamp. He envisioned it being produced in Tokyo as, “a collage of both Oriental theater and Western theater” (Cage and Retallack 2011, 341). The piece would incorporate all of Duchamp’s music along with an elaborate stage set that included the funnel/toy train apparatus. Nohopera was never realized.

In addition to his influence from Duchamp, Cage was also aware of Russolo’s activities, writing in 1946:

In several of its important aspects, modern music of the twenties is known only by hearsay. The Italian “Art of Noise” established by Luigi Russolo has totally disappeared, in memory it is mistakenly associated with Marinetti. The work done with speech orchestras, divisions of the half-tone and electrical instruments is, for the most part, forgotten. Many composers exist today only as names. (Kostelanetz 1970, 73)

When asked in 1961 to create a list of books that had the most influence on his thought, Cage listed Russolo’s The Art of Noise as number three of ten (Kostelanetz 1970, 138).

Cage began studying with Schoenberg in Los Angeles in 1935. Henry Cowell had encouraged Cage to acquire formal training in composition and suggested that he study with Schoenberg following preliminary lessons with Adolph Weiss, one of Schoenberg’s students and his former assistant. Cage idolized his teacher, stating at one point that, “he was not an ordinary human being,” but “superior to other people” (Kostalanetz 1991, 5). Cage repeatedly was quoted saying he worshiped Schoenberg “like a god” (Tomkins 1965, 85). While Cage was extremely dedicated to his teacher, Schoenberg’s teaching methods were autocratic and quite ruthless. As Cage described it, “he kept his students in a constant state of failure” (1967, 46). Perhaps the most famous interaction between the two came when Schoenberg stated that Cage had no feeling for harmony. To Schoenberg, skill in harmony was essential for a composer because it functioned as the central structural component of a musical work. Without a feeling for harmony, he warned, Cage would always be thwarted in his efforts to compose music by a wall obstructing the way forward. Recalling his promise to devote his life to music, Cage famously responded, “In that case I will devote my life to beating my head against that wall” (1967, 114).

Duchamp, Russolo, and Schoenberg all exerted a powerful influence on Cage, as did abstract filmmaker Oscar Fischinger. In 1936, Cage had been introduced to Fischinger, who commissioned Cage to write music for one of his films, and also hired Cage to be his studio assistant for creating animations. Fischinger suggested to Cage, “Everything in the world has its own spirit, and this spirit becomes audible by setting it into vibration” (Revill 2012, 40). “That set me on fire,” Cage recalled (Kostelanetz 1991, 8). “He started me on a path of exploration of the world around me which has never stopped-of hitting and stretching and scraping and rubbing everything” (Fleming and Duckworth 1989, 19). Cage’s embrace of a comment that could have been seen as an inconsequential claim is perhaps not only a confirmation of his predilection for experiment but also a first glimpse of his attraction to everyday sounds and experiences. “I began to tap everything I saw” (Kostelanetz 1991, 41).

Cage’s reimagining of music and his externalization of musical processes began with the introduction of noise through his use of percussion, asserting a democratized view of the materials of music. The composition of Cage’s early percussion works frequently utilized a technique of nested proportions (Cage 1961, 112), a numerical framework in which different aspects of the micro and macro structure were determined by the same set of numbers (Cage 1961, 57). In these early pieces, Cage was already demonstrating his approach to creating an autopoietic, algorithmic musical system. First Construction in Metal, for a percussion sextet, consists of sixteen large sections, each of which comprises sixteen measures based on the durational proportions 4:3:2:3:4. The proportional division 4:3:2:3:4 also applies to the grouping of the sixteen large sections (the macrostructure). The iteration of a numerical system on different time strata evokes the self-similar aspect of fractals, which are used to analyze complex systems in nature. The emergent properties of Cage’s early pieces, which utilize numerical processes to define the parameters of a composition, anticipated the practices of both the minimalists and algorithmic software composition by decades.

Cage’s exploration of the vocabulary of noise morphed into his practice of employing chance operations to compose his music. This was largely influenced by his engagement with Asian philosophies, further detaching composition from his own personal preferences and tastes. He also acknowledged Duchamp’s influence on his embrace of chance, “I always admired [Duchamp’s] work, and once I got involved with chance operations, I realized he had been involved with them, not only in art but also in music, fifty years before I was. When I pointed this out to him, Marcel said, ‘I suppose I was fifty years ahead of my time’” (Kostelanetz 1994, 219). Cage adopted the ancient Chinese oracular system the I Ching as a compositional tool in the 1950s. When asked by Kostelanetz if he incorporated the book’s predictive and guidance functions, he replied, “It’s not entirely separate from it, but I don’t make use of the wisdom aspects in the writing of music or in the writing of texts. I use it simply as a kind of computer, as a facility” (Kostelanetz 1991, 219). The I Ching provided a more complex system for Cage’s compositional processes, moving from the embedded numerical structures of his early works to the anarchic possibilities of randomness, which he implemented in a highly nuanced way (Burt 2014). Lochhead has pointed out how Cage’s embrace of chaos and randomness as positive values in his work can be viewed as an embodiment of chaos theory (2001). His usage of fractal structures as well as chance operations in his music affirms his lifelong desire to mirror the workings of nature (Piekut 2013), and his treatment of the I Ching as a computer to assist with composition points toward the algorithmic software applications that are becoming more and more widespread today.

The piece that best represents Cage’s challenging of music’s basic underpinnings and his prophetic vision of a totally inclusive musical future was 4’33”, also known as the silent piece. What more can be said of this work, which has generated volumes of criticism, analysis, and reflection? Cage himself regarded it as his most important piece, and stated that he always thought of it before writing his next work (Kostelanetz 1991, 66). Kyle Gann’s No Such Thing as Silence is an entire book devoted to 4’33”, in which he describes how “it begged for a new approach to listening, perhaps even a new understanding of music itself, a blurring of the conventional boundaries between art and life” (2017, 11). By opening music to include any sound, Cage fully realized his anarchic creative vision. Attali aptly described how 4’33” exemplifies the radical democratization of musical composition:

When Cage opens the door to the concert hall to let the noise of street in, he is regenerating all of music: he is taking it to its culmination. He is blaspheming, criticizing the code and the network . . . He is announcing the disappearance of the commercial site of music: music is to be produced not in a temple, not in a hall, not at home, but everywhere; it is to be produced everywhere it is possible to produce it, in whatever way it is wished, by anyone who wants to enjoy it. (1985, 136)

Cage’s ideal that the feelings and ideas of the composer should be emptied from music also permeates the performance practice, in that the traditional idea of a musical performer is subverted entirely. Each individual is viewed as a distinctly separate entity that follows her own time structure regardless of what anyone else is playing. Hierarchy is abolished and the musical organization is therefore completely democratized. The musical ensemble is transformed into a model in which everyone is concentrated on doing their own work as best they can without regard for anyone else. There are no principal, second or third chair players, everyone is equal and responsible only to themselves. When a conductor is used, in such works as Atlas Eclipticalis and Concert for Piano and Orchestra, that role is also subverted. The conductor functions strictly as a timekeeper, a human stopwatch, that has none of the interpretive and expressive functions of a conventional conductor.

Cagean Encounters

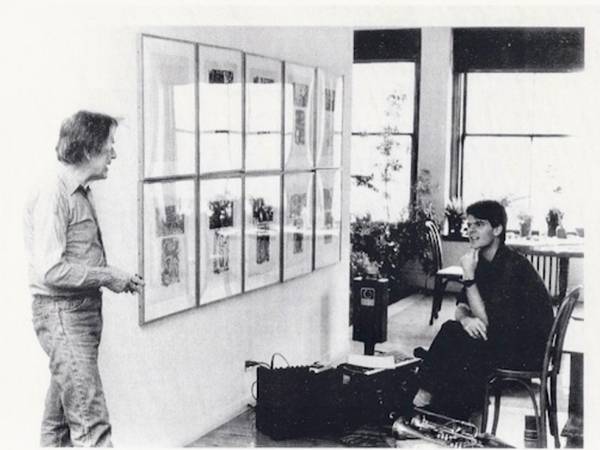

My personal experiences performing and working with Cage began in the 1980s with Petr Kotik’s S.E.M. Ensemble. I had first encountered Cage’s ideas while in high school in Winston-Salem, NC. My subscription to the Wake Forest University library was a window to the world in the mid-1970s, and while both Silence and A Year From Monday were revelatory for me at an early age, I didn’t hear much of his music until several years later. Kotik had a longstanding relationship with Cage and had worked with him on many projects. He took a very disciplined approach to performing Cage’s music, and I believe he remains the greatest interpreter of Cage today. Some of the most memorable experiences I had with Cage were working out the performance map for performances of Variations IV at Paula Cooper Gallery in SoHo, a 24-hour performance at WDR Köln commemorating his seventy-fifth birthday, an educational program at John Dewey High School in which Cage taught young students to create music spontaneously, and developing a Mutantrumpet version of his work Ryoanji for trombone, pictured here (see Figure 2.1).

Every style of music has a performance practice that is unique and not necessarily apparent, even if the music is specifically notated. In performing Cage’s music, musicians are asked to think in a way that is counter to everything they have been taught, that is, to not listen to what others are playing and remain entirely independent. While what the performers are asked to play is often unconventional, the performance instructions are often very specific in spite of the seeming philosophy of freedom and anarchy that underlies the music. Cage approached the unconventional, randomly generated elements of his pieces with a rigorous discipline that was no different from the precision of interpretation required for traditional, common-practice music. The goal was to empty out desire, but to explode possibilities to infinity. Kotik distilled Cage’s philosophy this way, “It’s not about what you want to do, but anything goes.” When Kotik and I worked with Cage to prepare a Variations IV performance at Paula Cooper Gallery, I asked Cage about the statement at the end of the score that allows “any other activity to go on at the same time.” His response was, “That’s the advanced version, after you’ve played it 20 times.”

Ben Neill rehearsing Ryoanji with John Cage in Cage’s apartment, 1986.

When playing Cage’s music, I always feel that the measure of a good performance is when the incidental sounds not being made by the musicians become part of the piece. The music literally erases all of the boundaries and hierarchies between art and life, performers and audience. A passing siren, a gust of wind, the rustling of the audience, or the heating system of the performance space all become elements of the musical fabric. While the Zen-like psychological state that I experienced while performing Cage’s pieces was uniquely liberating, at times I felt it was lacking the ecstatic element that I found from musical performances in which connecting and blending with other musicians were the focus. Cage performances were thrilling in the way they released the performer from traditional sound-making, and the coincidental sequences and simultaneities were often fascinating. However, I found performing Cage’s music to often be a rather lonely experience, a bit like being around a group of people who are very advanced linguists, none of whom are speaking the same language.

By eradicating the ego, Cage succeeds in emptying out previous models for social interaction, both for performers and audiences:

It is hard to claim that 4’33” is musical from an ontological point of view, for it can only be interpreted as music at an individual level with absolutely no guarantees that it will be by all individuals—and 4’33” exemplifies this last point perhaps better than any other piece in the history of music. (Hainge 2013, 58)

I encountered the power of Cage’s music to challenge existing norms directly in 1986 when I performed the Solo for Trumpet from Concert for Piano and Orchestra along with the electronic composition Fontana Mix on a juried recital at Manhattan School of Music. These pieces were composed in the mid-1950s but, perhaps unsurprisingly, had not yet made their way into the domain of conservatories. When I brought the score for the piece into a private lesson in preparation for the recital, my teacher looked at it and asked disdainfully, “What is this? What is this piece?” I explained the origin and was reluctantly allowed to program it on my recital, which was graded by a jury. My performance of the piece was done on the Mutantrumpet along with several other trumpets and attachments, including a hose connected to a gramophone horn and a bucket of water, which I played into with the slide of the Mutantrumpet. The performance generated quite a bit of controversy, with at least one member of the jury so upset about it that he did not want to allow me to pass and receive my degree. The objection to the performance was that Cage’s piece was mocking or poking fun at the classical music establishment, even thirty years after it had been composed. This came as a surprise to me, since I had approached the preparation and performance of the Solo for Trumpet with the same attention to detail and accuracy as the other more traditional pieces presented on the concert. In the end, I was allowed to pass and be awarded my degree, but the episode demonstrated how the revolutionary quality of Cage’s music and ideas sustained for decades following its creation.

Cage’s compositional ideas were truly prophetic in their foreshadowing of the way music would become externalized and democratized through digital technology and ICTs. In addition, he repeatedly made direct statements that advanced the idea of technology facilitating the redefinition of music and art as collective in nature:

[W]e live as the effect of electronic inventions by means of which our central nervous systems have been exteriorized . . . The world we live in is now a global mind. (Kostelanetz 1970, 170)

Our present technology, according to McLuhan, is the extension of the central nervous system, so we’re in a situation of a greater number of ideas and interconnection of ideas. (Lohner 2001, 268)

What we need is a computer that isn’t labor-saving but which increases the work for us to do, that puns (this is McLuhan’s idea) as well as Joyce (this is Brown’s idea) revealing bridges where we thought there weren’t any, turns us (my idea) not “on” but into artists. (1967, 50)

Computers are bringing about a situation that’s like the invention of harmony. Subroutines are like chords. No one would think of keeping a chord to himself. You’d give it to anyone who wanted it. You’d welcome alterations of it. Subroutines are altered by a single punch. We’re getting music made by man himself, not just one man. (Kostelanetz 1970, 209)

Cage also described the possibility of “a computer that acted more like nature than like human beings,” indicating a strong impulse on his part to collapse boundaries between nature and machines (Dunbar-Hester 2010, 121). His use of algorithmic and autopoietic processes represent another example of creative ideas anticipating or necessitating technological development. In the 1950s he met Lejaren Hiller, who is considered the first composer to use a computer to write music in his string quartet, Illiac Suite (Ariza 2011). Each of the piece’s four movements was created with a separate computer program that implemented a different algorithmic process. While its premiere at the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana was met with audience outrage, today the work sounds genial and even lyrical. Its steady, motoric rhythms resemble the sequenced patterning of minimalism and popular electronic music, and its harmonic structure incorporates tonal and modal structures with occasional dissonances. The programming of the piece incorporated rules from Palestrina’s sixteenthcentury counterpoint, which gives the linear and harmonic movement a familiar sonority (Hiller 1959). Ironically, this pioneering work does not appear among the 100 million tracks available today on Spotify!

In 1967, Hiller invited Cage to be a visiting professor, which included working in the Experimental Music Studio at the University of Illinois. Hiller had established the studio in 1952 and had invited Cage to curate an international electronic music concert there, which Hiller referred to as the first of its kind in the United States. Cage accepted the visiting position, and the two began collaborating on work titled HPSCHD. Cage had been commissioned by a Swiss harpsichordist to create a piece for harpsichord with computer sounds. He wanted the piece to be an homage to Mozart, which would include quotations from Mozart’s music played on the harpsichord, as well as referencing Mozart’s use of dice games, which was discussed in Chapter 1.

HPSCHD utilized three computer programs: one for composing the recorded microtonal tape music, another for creating harpsichord parts derived from Mozart’s Musical Dice Game to be played live, and a third for generating a score to accompany the Nonesuch Records recording of the work. This aspect opened up the piece to audience participation by providing instructions for raising and lowering the volume and tone controls on a home stereo system, creating an interactive experience decades before the concept was widely understood. The use of quotation was a prototype for sampling, which would also become part of mainstream musical practice decades later.

Unlike Illiac Suite, the sound of HSPCHD is a disjointed, noisy collage that many have found impenetrable due to its extreme dissonance and sonic quality. Occasionally the references to Mozart are perceptible, but the work also quotes material from Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann, Gottschalk, Schoenberg, Hiller, and Cage himself. The program described the performance of the work,

Twenty-minute solos for one to seven amplified harpsichords and tapes for one to fifty-two amplified monaural machines to be used in whole or in part in any combination with or without interruptions, etc., to make an indeterminate concert of any agreed-upon length having two to fifty-nine channels with loudspeakers around the audience . . . In addition to playing his own solo, each harpsichordist is free to play any of the others. (Cage and Hiller, 1969)

The premiere included large-scale projections of 6,400 slides on sixty-four projectors and eight film projectors playing forty films, reflecting the sixtyfour hexagrams in the I Ching. The visual presentation included graphics of the I Ching and images of space travel obtained from NASA via Cage’s friend Buckminster Fuller, all structured through algorithmic processes. The event was attended by nearly seven thousand people (Husarik 1983). Richard Kostelanetz described it this way:

All over the place were people, some of them supine, their eyes closed, grooving on the multiple stereophony. A few people at times broke into dance, creating a show within a show that simply added more to the mix. Some painted their faces with Dayglo [sic] colors, while, off on the side, several students had a process for implanting on white shirt a red picture of Beethoven wearing a sweatshirt emblazoned with John Cage’s smiling face. (1970, 175)

The performance of HPSCHD resonated with the performance activities that came to be known as Happenings, which Cage had pioneered in 1952 with his Theater Piece, presented during the experimental summer courses at Black Mountain College in the mountains of North Carolina. Happenings combined multiple art forms and activities, blurring the distinctions between performers and audience and challenging norms of presentation. Allan Kaprow and the Fluxus movement continued to develop Happenings in the 1960s, and the events were essential to the democratization of artistic performance. These events were the foundation of what came to be known as performance art, and Cage played a major role in their original formation.

Anarchic Harmony

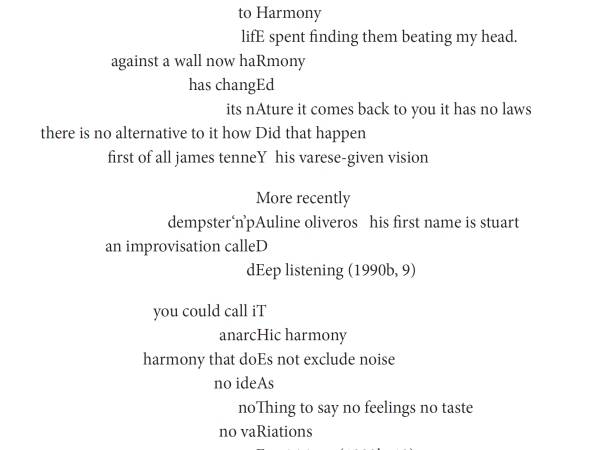

Throughout his life, Cage’s ideas were exemplary in their uncanny ability to project the future in prophetically radical ways. His last pieces and writings from the late 1980s articulate ideas that are particularly relevant to our time. From 1986 to 1992 he wrote forty-eight compositions commonly known as the Number Pieces. These works were usually scored for conventional Western instruments and standard pitches, and many of them exhibit a meditative delicateness that is reminiscent of the music of Pauline Oliveros or La Monte Young. The Number Pieces were composed using computer-based systems designed by Andrew Culver for the indeterminate elements. A system that Cage termed “time-brackets” (Emmerik 2001, 162; Weisser 2003) was used to structure the linear progression of the music. Using a stopwatch, as is required in many of his pieces, the performers are given a range of timings in which they can enter and exit with each sound or gesture, maintaining the democratization of individual performance practice that was present in his works since the 1950s. Silences which occur unpredictably are also incorporated. These processes are combined in the Number Pieces to create what Cage termed “anarchic harmony” (Swed 1993, 140). A mesostic that he delivered in Darmstadt in 1990 described his new concern with this aspect of music that had originally been presented by Schoenberg as a brick wall blocking his development as a composer (Swed 1993, 142).

It is fascinating that Cage turned toward a concern with harmony and often limited the sonic palettes in these works. His interest in vertical relations was inspired by the music of composers James Tenney and Pauline Oliveros (Weisser 2003), and the spine of the first mesostic excerpted above spells out The Ready Made Boomerang, the title of a piece by Oliveros’s Deep Listening Band. The Number Pieces balanced Cage’s interest in anarchy, randomness, and indeterminacy with sonorities and durations that were more characteristic of standard musical expression than most of his previous output. They present a stark contrast the exploded vocabularies of his earlier chance-based works. The concept of anarchic harmony has profound, far-reaching implications for our time. Swed points out that, “with anarchic harmony, Cage finally crossed over that wall that Schoenberg had set before him, and, with a superb ironic joining of the historical circle, he did so by following Schoenberg’s own desire for a harmony without hierarchic relationships to its ultimate conclusion” (1993, 142). The Number Pieces present a model of anarchy that has essentially been tuned, while still making use of the indeterminacy that Cage valued so much. They offer a musical model for our current state of information overload and mental atrophy as defined by Bhatt (2019). In the Number Pieces, musicians are still allowed to make creative choices that contribute to the outcome of the performance, but the sonic materials present a range of possibilities that is much less anarchic in nature.

Cage and Norman O. Brown

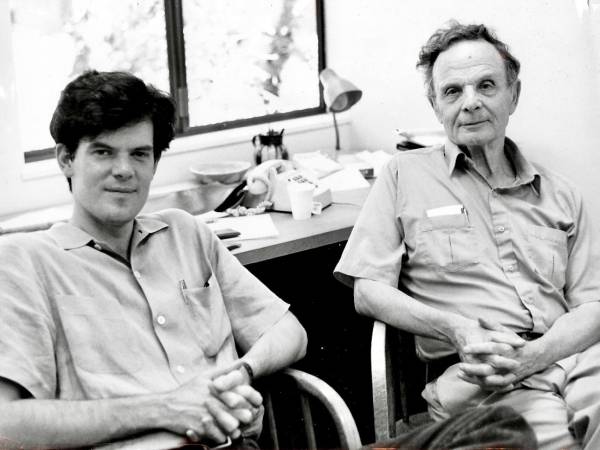

One of Cage’s many collaborators during the 1960s was the philosopher and classics professor Norman O. Brown. Cage’s references to Brown in his writings, along with recommendations from several of my musical collaborators, led me to explore Brown’s books Life Against Death and Love’s Body in the 1970s. Brown espoused a Dionysian view of history and culture that focused on integration and unity. His style of writing was extremely compelling to me, and his ideas aligned with my instinctual creative impulses, which were focused on synthesis, hybridity, and the breakdown of artistic hierarchies. His 1968 book Love’s Body is written in a fragmented style that strings quotes from far-flung sources together into a provocative stream of consciousness, a kind of proto- mashup of literature. Brown’s writings were some of the most formative in my creative development, and in 1990, after a brief correspondence, I made a sojourn to Santa Cruz to meet him in his office amidst the redwoods. We talked extensively about his relationship with Cage, and he described how he had felt the need to distance himself from the composer a couple of years before at a symposium on the occasion of Cage’s seventy-fifth birthday. Simply titled John Cage, Brown’s contribution to the event is written in the same style as Love’s Body, collaging quotes from several of Cage’s books as well as other disparate sources including Attali. Brown felt that Cage’s approach to music and the use of chance was too Apollonian, asserting his preference for a Dionysian ideal of art, music, and culture. In our conversation he talked about the need for impiousness, and his current fascination with hip-hop, which was shocking! (see Figure 2.2).

Ben Neill with Norman O. Brown in his office at UC Santa Cruz, 1990.

Brown’s notion of a Dionysian urge to unity is diametrically at odds with Cage’s approach to composition and social models in which structures emerge incidentally as a result of individuals’ contiguous, uncoordinated activities. In an address in which he distanced himself from Cage, Brown stated, “I don’t think it is true that nothing is accomplished by listening to a piece of music. The events of this week will bear me out. Our ears will be in much better condition” (1989, 99).

Brown is asserting that Cage’s music still has value, even though it points toward a future in which no one needs composers or music. Shultis has explored the relationship of Brown and Cage extensively and points to a 1958 interview with Cage on the television show 60 Minutes in which he said, “Those artists for whom I have regard have always put their work at the service of religion or of metaphysical truth. And art without meaning, like mine, is also at the service of metaphysical truth. But it puts it in terms which are urgent and meaningful to a person of this century.” Moderator Mike Wallace responds: “Meaningful? But you said it has no meaning.” Cage: “But I mean no meaning has meaning.” Wallace: “Oh?” Cage: “Yes. This idea of no idea is a very important idea” (Shultis 2006, 71).

Brown quotes Nietzsche to contrast the Apollonian and Dionysian sensibilities that he alludes to in his writing:

Nietzsche says the word Dionysian means the urge to unity, a reaching out beyond personality, a passionate-painful overflowing: the great pantheistic principle of solidarity and sharing; the eternal will to procreation, fertility, recurrence; the assertion of the necessary unity of creation and destruction. Apollonian means the urge to perfect the separate life of the individual, to compensate for the pain of separate individuality with the seductive pleasures of aesthetic enjoyment. (1989, 108)

Ironically, at the end of their lives, Brown and Cage’s positions had actually inverted. Brown accepted Cage’s articulation of randomness as the primary mode of experience, while Cage created his most organized and harmonious works. In his interview with Dale Pendell near the end of his life, Brown states:

NOB: I am looking at chance, I think that life is an accident.

DP: Welcome to the twentieth century.

NOB: The old NOB, of Love’s Body, where I differed from Cage—I think now that NOB was wrong and that John Cage was right. (2007, 3)

While in his 1990 lecture at Darmstadt, Cage stated, “I no longer consider it necessary to find alternatives to harmony, after all these years I am finally writing beautiful music” (1990b, 8).

Was it really Cage’s idea to eradicate composers, or was his challenge rhetorical? Are everyday sounds just as interesting as those of the concert hall, including his? And if so, did he have any idea how pervasive his ideas would become? For me, the Dionysian impulses toward unity and fusion described by Brown have proven to be more compelling as a guiding artistic philosophy than the detachment of Cage’s Apollonian sensibilities. However, both attitudes offer legitimate insights in approaching the question of how to navigate the diffused, “anarchic society of sounds” in which we are currently living.

This article is based on the chapter Systematic Anarchy from the book Diffusing Music: Trajectories of Sonic Democratisation by Ben Neill. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2024. With kind permission from the publisher.

Ben Neill

Ben Neill is a composer/performer, author, professor, and inventor of the Mutantrumpet, a hybrid electro-acoustic instrument. He blends ambient soundscapes created with live sampling, dynamic electronic grooves, and real-time video control to produce “art music for the people” (Wired). He has released fourteen albums on labels including Verve/Universal and Astralwerks, and his extensive performances include BAM, Lincoln Center, and Big Ears. Diffusing Music is his first book, published by Bloomsbury Academic in 2024.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Ben Neill

Ben Neill

Ben Neill