23 Minuten

When nothing works: repeat repetition.

The concept of repetition, with all its theoretical weight, also stands for the obsessive and the humorous. While the paradigm of repetition has been questioned for decades by avant-garde art and music in order to problematize traditionally prevailing opposites such as original and copy, authenticity and fake, in other areas of (pop) culture it has developed into a fragmented, hedonistic gesture that cultivates the beauty of the serial and repetitive. As different as the works from the fields of art, pop culture, film, music, everyday life, theory and practice discussed and shown here are, they have in common the fact that they each focus on and undermine the classical categories of identity and subjectivity in a specific way..1

In this article, I will concentrate on Cold Trip and the compositional strategies and concepts associated with it. I am now working on further series, some of which are very different from the monadologies, but I will not discuss them here.

- 2015, Monadology XXXI 'For Franz III' for zither and string quintet [25'], after Schubert's C major quintet

- 2012, Monadology XXI '...for Franz II' for flute, cello and quarter-tone accordion [15'] (after Schubert op. 99)

- 2012, Monadology XX '...for Franz I' for piano trio [20'] (after op.100)

Looking back at the Monadology series today, the Cold Trip marks a turning point: the earlier Monadologies processed my own and historical scores with computer programs; I had already processed two Schubert scores in this way by this point (Trio E flat major, Trio B flat major).

In the course of the work, I had already internalized these processes, which I had to repeat countless times, to such an extent that using the computer became redundant and I was able to carry out the editing virtually freehand. This was already the case when editing Cold Trip and also when composing for Franz III.

Originally, I had assumed that using the computer would shorten the composition time; in fact, however, I needed much more time to evaluate, discard, repeat, cut, select, etc. the results of the processing. When working with the algorithm, it is very important not to be tempted into absolute belief in the result.

The psychological impression of coherence and correctness that the machine's precision conveys does not necessarily correspond to aesthetic coherence. Here, historical and aesthetic a posteriori filtering is necessary to achieve what Schönberg somewhat mystically calls “musical logic”: something that we all know, but don't know what exactly it is.

A good example of this is the dramaturgy of times and durations. There is a very precise sense of excess length. You often feel an ending in a piece that is not the actual ending. You don't really know why that is, and yet it is necessary to approach the result of an algorithmic composition with precisely these criteria.

Nevertheless, some elements of algorithmic procedures can be recognized in Cold Trip:

- the monadological principle: i.e. the cutting out of singular cells from the original text: the selection is intuitive, as in the sampling of a hook line; the cutting out is a virtual sampling process, where a score or a MIDI file is used instead of audio/video material.

- The repetition of the sample: looping in all its forms. Repetition replaces evolving narrative as a means of prolongation.

- Continuous sampling frequencies: pulses and beats: grid operations.

To shed more light on the concept of Cold Trip, I would first like to discuss the idea of overwriting that precedes all monadologies.

As paradigmatic examples, I would first like to take a closer look at Monadology XIII the saucy maid (after Bruckner's First Linz Version), which precedes the Cold Trip, and the complete overwriting of Parsifal, which follows the Cold Trip.

- 011-2012, Monadology XIII 'The Saucy Maid' for 2 orchestral groups in a quarter-tone scale (after Anton Bruckner's 'Linzer Sinfonie - Das Kecke Beserl' ) [ 60'] commissioned by the Donaueschingen Music Days 2013

- 2015-2016, ParZeFool music theater for voices, choir, ensemble and 2 jazz musicians [200'] based on Richard Wagner's Parsifal. Wiener Festwochen/Theater an der Wien 2017

ParZeFool (Der thumbe Thor)

Kurzer Hinweis auf die Beziehung zwischen Wagners Originalpartitur und der daraus entstandenen Komposition in Bernhard Langs ParZeFool.

A brief note on the relationship between Wagner's original score and the resulting composition in Bernhard Lang's ParZeFool.

The entire piece follows:

- Wagner's temporal structure, which ranges from the overall structure of prelude/3 acts/2 pauses to the length of the individual “scenes”, resulting in a total length of about 200 minutes.

- Wagner's text: This is transformed by:

- translations into French (flower girls), English (Amfortas), Hebrew (choir)

- abridgements of “key texts”, omissions of longer narratives (Gurnemanz)

- repetition of hooklines “redemption to the redeemer” - Wagner's narrative with subtle changes and transformations of relationships and persons (Kundry wins)

- Wagner's characters, with the omission of Titurel and the reduction to 4 flower girls; a squire is sung by a soprano, Parsifal by a countertenor. The whole piece follows my technique of difference/repetition, which I have applied in Theater of Repetitions, I hate Mozart, Montezuma, Der Reigen, Der Golem.

On June 8, 2017, the premiere of MondPARSIFAL/ParZeFool took place at the Theater an der Wien: This is a complete rewriting of Wagner's Parsifal that follows the original text and time structure:

- It is the first time that a complete opera has been rewritten in this way.

- The term “rewrite” does not seem to cover all the meanings of the German term “Überschreibung”, which also includes the concept of the palimpsest..2

- When we started our collaboration with Jonathan Meese, we decided to:

- keep the original time frame (including the absolute length of 200 minutes)

- keep the original libretto

- keep the original actors (renamed as: ParZeFool, Cundry, Amphortas, Clingsore) - Keep the plot

I. Overwriting

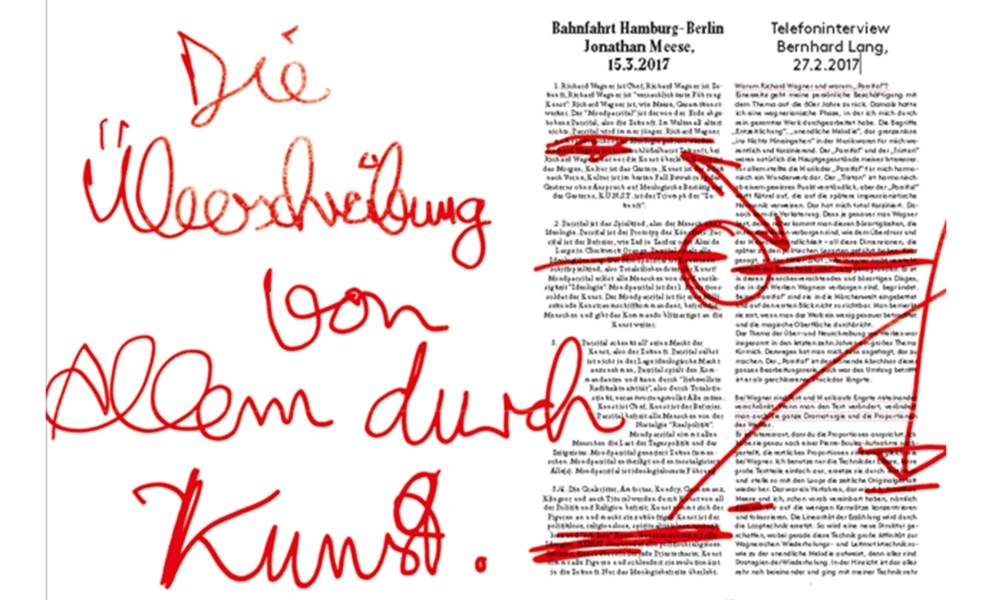

In Meese's work, the concept of overwriting plays a decisive role, as do the concepts of inscription and marginalia.

During our collaboration, there were several phases of overwriting:

- Meese tries to overwrite Parsifal in Bayreuth, is thrown out.

- I overwrite Wagner's score:

- the libretto, adding marginalia, comments, shifts in meaning (“redemption from redeemers”)

- the score, starting with the piano reduction (see scans) - Meese overwrites Lang, adds Lang's subtitles

This is also reminiscent of Arnulf Rainer and his overpaintings:

Overwriting is also an aspect of Appropriation Art.

This concept starts from the idea that text is always structured like an onion: there are first layers, second layers and so on; this refers to the idea of interpretation itself, taking the original text as the starting point, as in Jewish textual interpretation.

Furthermore, the absoluteness of the first writing is replaced by the beginning of a discourse between the layers of writings, so that the original writing is deconstructed, overlaid and charged with new meanings.

This discourse not only produces new meanings of the original text, but also questions:

- the concept of the original

- the notion of the author himself and, furthermore, that of the subject

- the notion of the new in the context of creation (particularly interesting in the context of “new music”).

I distinguish between:

- the “First Writing”

- “Second Writing”.

This means that the first writing is regarded as absolute, corresponding to the pre-critical view of the text or composition; it correlates with the ingenious writer of the Romantic period; the second writing corresponds to the critical view/reading, with the first serving only as a starting point for the discourse that leads to the act of overwriting.

Overwriting is a technique of metacomposition

Instead of creating a new texture out of nothing, metacomposition starts with an existing work; in a way, it could be compared to the concepts of non-philosophy (Laruelle); it could also be called non-composition.

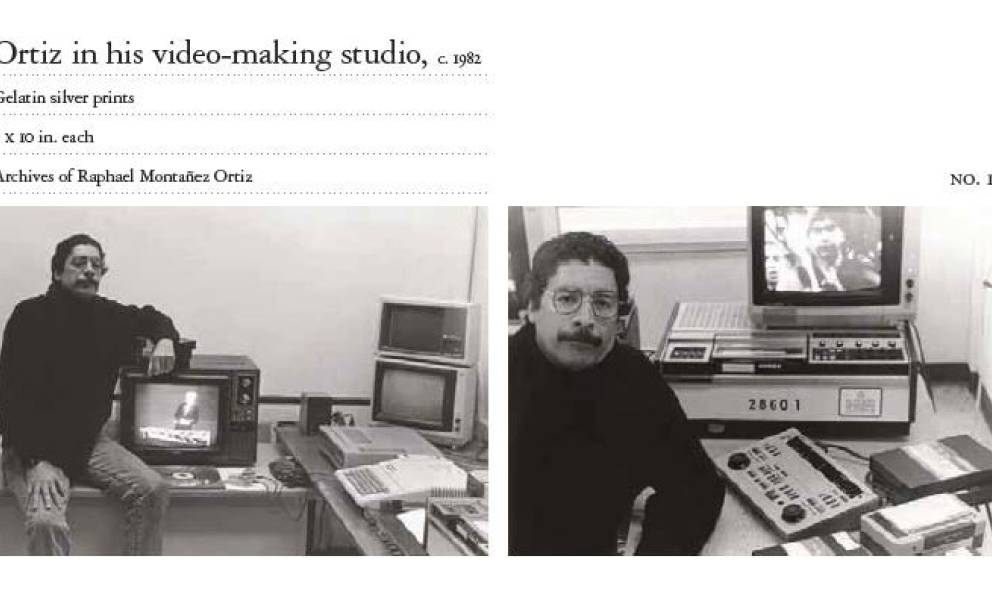

I was inspired by the Austrian school of meta-film (Deutsch, Kubelka, Brehm, Arnold, Pfaffenbichler) and the American artist Raffael Montañez Ortiz.

The reference to film leads us directly to music theater, and as Alexander Kluge pointed out, Bayreuth was the forerunner of IMAX cinemas.

When I composed Theatre des Répétitions, it became clear to me that the transfer of meta-film techniques works best with human actors and theatrical staging. This was the first attempt to transfer Martin Arnold musically.

At that point, I didn't dare to use parts or even the whole work, although this was the logical consequence that I could only draw in 2016.

II. Repetition of the Repeats / The Loop

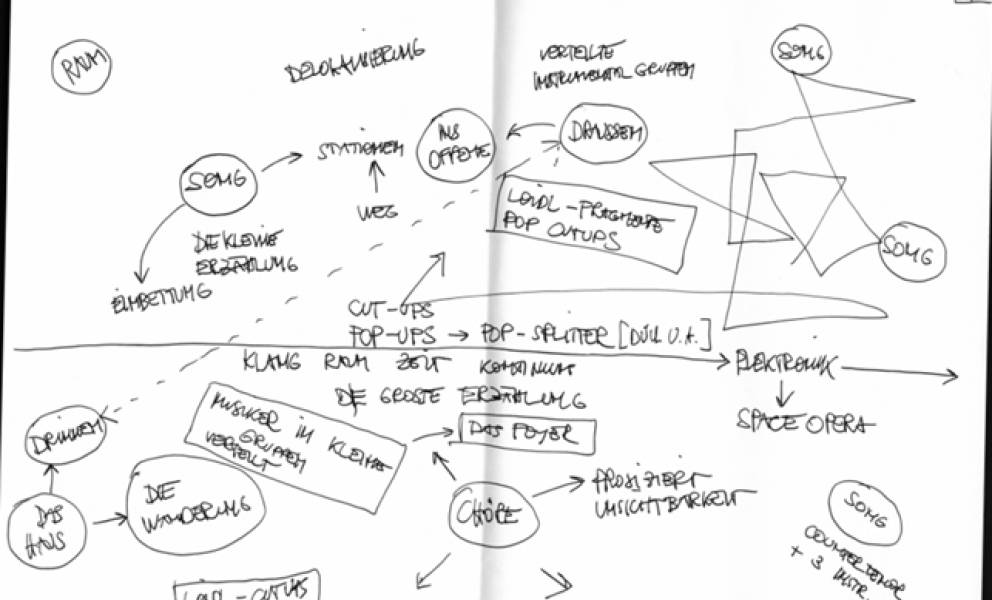

What I have created here is a kind of virtual remix of the score, in which remix techniques (looping, cutting, layering) are applied to scores in MIDI format.

The repetition of the original Wagner essentially takes place on two levels:

- repetition of the historical repertoire/archive

- use of differentiated repetitions as a compositional device within the work.

The role of the loop becomes crucial:

ParZeFool is a LoOpera, a piece based on repetition

ParZeFool is a LoOpera, a form of music theater based on repetition, which is based on theater of repetition.

“The theater of repetition is opposed to the theater of representation, just as movement is opposed to concept and to the representation that traces it back to the concept. In the theater of repetition, we experience pure forces, dynamic lines in space that act directly on nature and history, without the mediation of the mind, with a language that speaks before words, with gestures that develop before organized bodies, with masks before faces, with ghosts and phantoms before characters – the entire apparatus of repetition as a “terrible power”. (DR, p.7, introduction)

My aim was to create a new form of music theater that would implicitly criticize the new concepts I was familiar with. I contrasted the theater of repetition with the theater *of representation as a critical antithesis. In a sense, opera is always representative theater, both in terms of the definition of identity in the story being told and in terms of the definition of the performers' identity, but also in terms of the political identity of the power-holders represented in the music theater. The term theater of repetition comes from Deleuze, who cites it in the introduction to Difference and Repetition, as the focus of “pure energies”.

Nam June Paik and Peter Roehr. Elvis Presley and Karlheinz Stockhausen. The Beatles and Andy Warhol. Terry Riley and Ken Kesey. All these artists have in common the fact that loops have played a significant role in their works. In art and music after the Second World War, short audio or video sequences repeated with the help of recording media have proven to be an astonishingly flexible, versatile, and consequential aesthetic method. Today, loops must be counted among the most important means of creating postmodern art and music. Yet until now they have been largely overlooked as an aesthetic phenomenon. This book tells a secret story of the 20th century for the first time: how a formerly inconspicuous basic function of all modern media technology has produced complete artistic oeuvres, music styles such as minimal music, hip hop and techno, and, most recently, entire scenes and subcultures that would have been unthinkable without loops. 3

Ich hatte mich in meinen Musiktheatern schon zuvor mehrfach auf Wagner bezogen:

retro

spatial installation for Wagner loops and a dancer

sitting in the living room – listening to music – getting up – going to the window – :

traces of everyday repetitions, drawn into the imaginary futurity of a habitat.

going backwards :

into domestication

into habit

into a veiled existence, existence veiling

into the security of the unconscious.

Bernhard Lang, 5/12/2004

Hanging Gardens an interdisciplinary project by Cie.Willi Dorner and guests, 05.08.-07.08.04, 6:00 pm

BUWOG residential complex “Hängende Gärten”, Dr.-Herta-Firnberg-Straße 7, 1100 Vienna

ImPulsTanz04

- 2007, MOSAIK MÉCANIQUE, music/installation for the film by Norbert Paffenbichlers, www.pfaffenbichlerschreiber.org, (tristan and isolde/Stan and Oliver)

- 2007 -2009, Montezuma Fallender Adler, music theater based on texts by Christian Loidl, commissioned by Linz 2009

Here in the second scene, Parsifal is quoted when Montezuma hands over the drug to the priest Damian.

The last act begins with Tristan, Act III, prelude.

In addition, Mozart was overwritten in I hate Mozart and The Stoned Guest.

- 2006, Odio Mozart / I hate Mozart, music theater in two acts, libretto: Michael Sturminger, Vienna Mozart Year 2006.

- 2013, Monadology XXIV 'The Stoned Guest', short opera for 3 voices, flute, clarinet, cello, accordion, percussion [15'] Commissioned by ISCM

III. Looping Wagner / Overwriting Parsifal - the method:

- selection of hooklines/text loops: reduction of the Wagner libretto to essential motifs/words

- Generation of loops from hooklines (piano extraction);

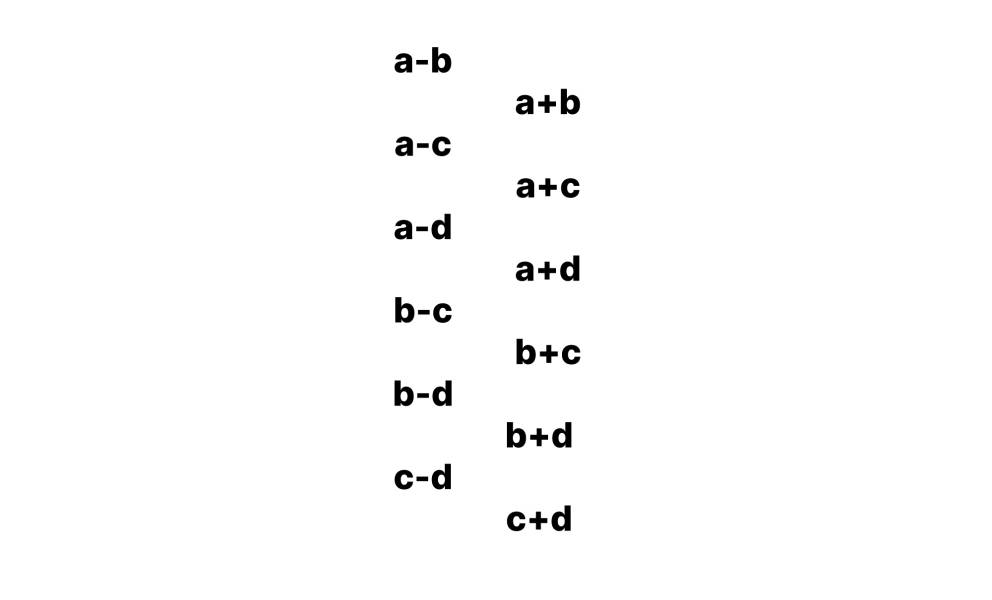

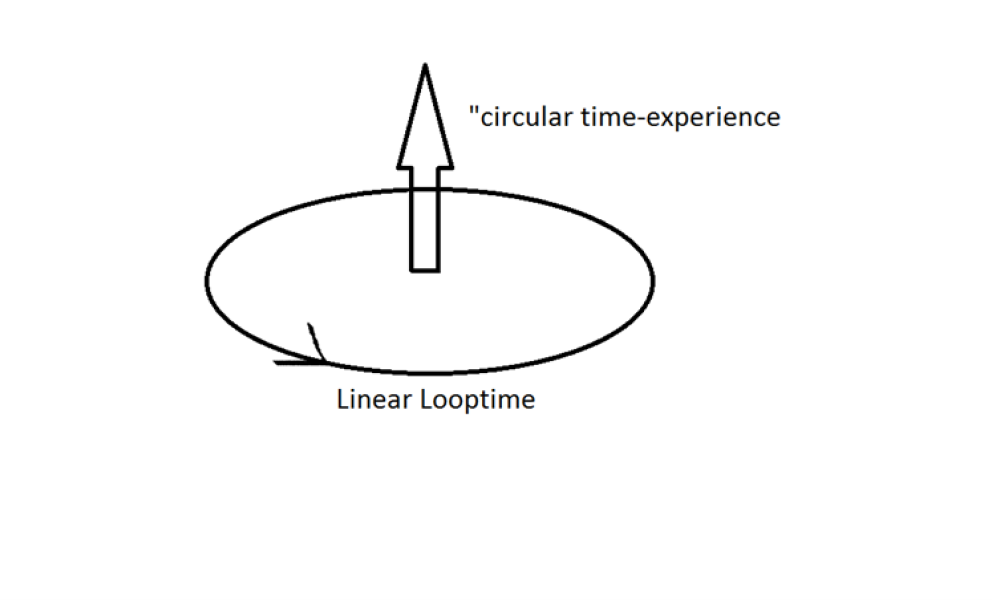

- Generation of 12 sum/difference tones from four-part Wagner harmony:

4. Fitting the resulting harmonic loops into the original Wagner timelines, taken from CDs (eventually from the Boulez recording).

The original timeline used in the composition of ParZeFool.

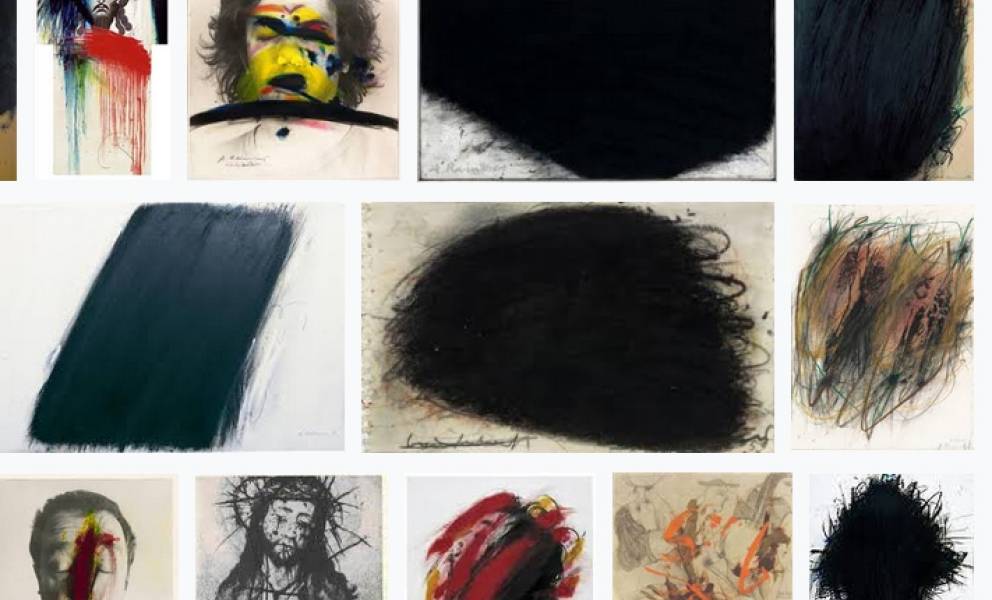

Jonathan Meese, Parsifal - 2016

The Monadologies: Virtual Remix

Mainly inspired by Deleuze (Milles Plateaux, The Fold), I discovered the concept of monadology4 as a descriptive model for my techniques5: Whereas I had previously used audio and video material with various loop generators, I now shifted all editing to scores (as MIDI files); I programmed a MIDI-based score sampler and synthesizer6, that virtualized the loop machine and created a kind of abstract long machine. (Cf. the concept of the abstract machine in Deleuze in 1000 Plateaux.7

Harmony of Difference

See also Bernhard Lang's list of works.

Excerpts from Time-Loop/Loop-Time, Berlin 2016

II.1 Definition

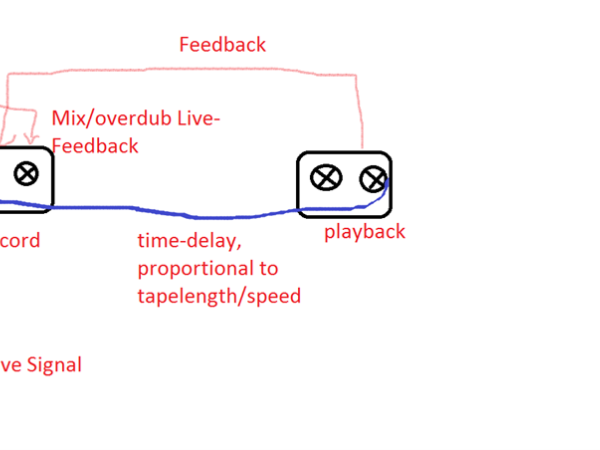

- A loop is a structure in which the end is connected to the beginning. (cf. early tape loops)

- Looping the loop: This introduces a kind of movement:

By running/reading/playing this structure, you get to the end and jump back to the beginning: a different structure emerges, which we perceive as repetition.

The loop consists of the following basic parameters (here in a simplified way):

- Loop start in time

- Loop end in time

- Loop content (information)

- Reading speed (e.g. sample rate)

- Reading direction

- Reading mode a) linear b) chaotic (scratching)

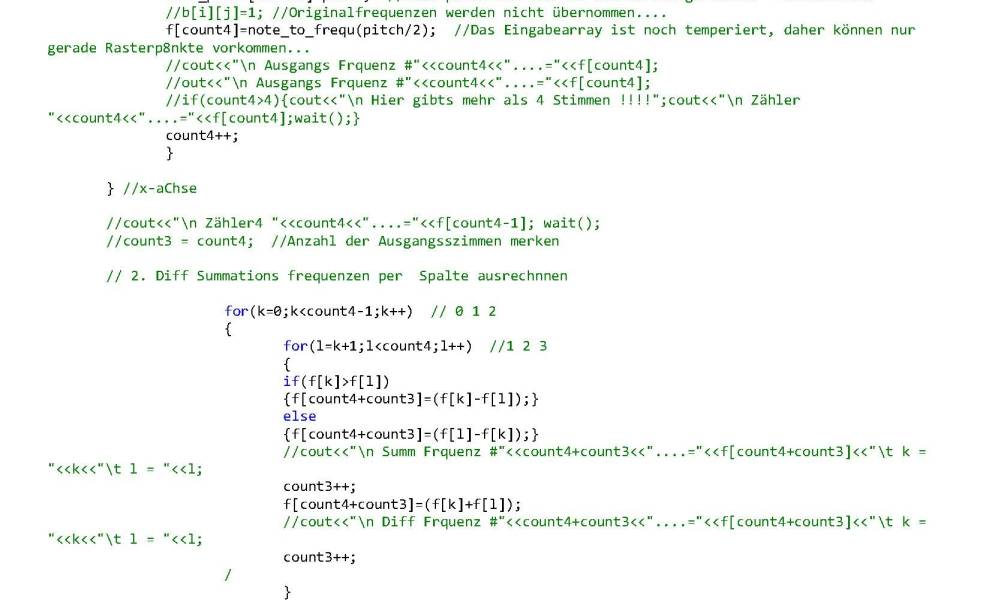

In the context of digital media, the loop is paired with a complementary term, the sample, a time-limited piece of information; this sample can be described as a section of computer memory that is read. (here it replaces the loop content).

This seems an inappropriate use of the term “reading', but it changes everything in the artistic approach to the loop in the 1980s.

The double-term loop-samples or sample-loop contains a double repetition, namely:

- the repetition that is contained in the loop process

- the sample as a repetition of something given, already existing.

In computer languages, the loop is a standard function:

for(i=0;i<2016;i++){cout<<„this is a loop“;}

this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is a loop this is Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife Dies ist eine Schleife

{cout<<„wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: wiederholung wiederholen“; day++: }

wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: Wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: Wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: Wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: Wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: Wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: Wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: Wiederholung wiederholen wenn sonst nichts mehr geht: Wiederholung wiederholen

II.2 Typology:

A) A difference in time span

- Granular loop 50 ms to 200 ms

- Short-duration loop 200 ms to 7000 ms (long Fuga soggetti)

B) A difference in modulation

We have to distinguish between modulated and unmodulated loops.

Unmodulated loops:

- Modulation of the loop start (Ortiz or Arnold's hiking loop) This is a very specific loop that became important in video art in the 1980s. I coined the term “granular analysis” for this technique.

- Modulation of the loop end (often in combination with start modulation

- Modulation of loop content (filter, iteration, feedback)

- Modulation of reading speed (scratching)

- Modulation of reading direction (scratching)

Iterated or feedback loops represent a species of their own, which is not sufficiently expressed in this categorization. They often represent dynamic systems that frequently use iteration (cellular automata, fractals, etc.)

I distinguish between global changes/modulations and local modulations:

- Global modulations change the number of iterations, e.g. a filter opens at the first and at the 10th iteration

- Local modulations change the value within each iteration. The filter opens and closes within each iteration.

There are different modes of modulating parameters:

- Increment

- Decrement

- Jitter: A range of epsilon is defined within which the modulated loop point moves back and forth erratically, often controlled by a randomizer

- Oscillation: The specified loop point moves rhythmically back and forth within a range of epsilon.

C) Difference in smoothness

- Smooth loops: the jump point is disguised (e.g. a loop that is evenly filled with noise or the jump point is not recognizable in the information)

- The hiccup loop: the jump point is exposed (e.g. Pierre Schaeffer's fixed plate or Phil Jeck)

D) Difference by reference to the sample

- Loop refers to the archives (real or virtual remix)

- loop refers to newly created information (e.g. improvisation, composition)

E) Difference by medium 1 Visual Loops

- Visual Loops

- Audio Loops

- Body Loops

- Text Loops

- Combinations of 1-4

F) Difference by historical context

- Analog (joining tapes, cutting and pasting film clips)

- The difference becomes clear with film clips: while analog looping had to be created as a sequence of clips (except for the rare actual film loops, the digital loop is created by repeatedly retrieving the same section in the computer RAM)

- Digital (see Harry Lehmann The Digital Revolution of Music)

- here the loop becomes an essential module within the digital editing program

G) Difference in complexity

- Complexity of content: In Minimal Art, the primary information content of loops is rather minimal, with the focus being on changes in perception. The loops in the 90s contain very complex information, which could be the reason why Feldman, on the one hand, was a loop composer but was never considered a minimalist. The same applies to Phil Jeck's loops.

- Complexity of repetition: While minimalist loops tend to be very linear, predictable (or not at all), complex loops develop in an unpredictable, chaotic way (e.g. scratching).

- Complexity of content modulation: Especially feedback loops like Robert Fripp's “Frippatronics” can generate extremely complex systems from simple initial conditions, which Stephen Wolfram often mentions.

Most models of dynamic systems are based on interacting loops.

Another example is a video stream with feedback (Douglas Hofstaedter “I am a Loop”: here, feedback loops are discussed as a model of the self-reflective subject).

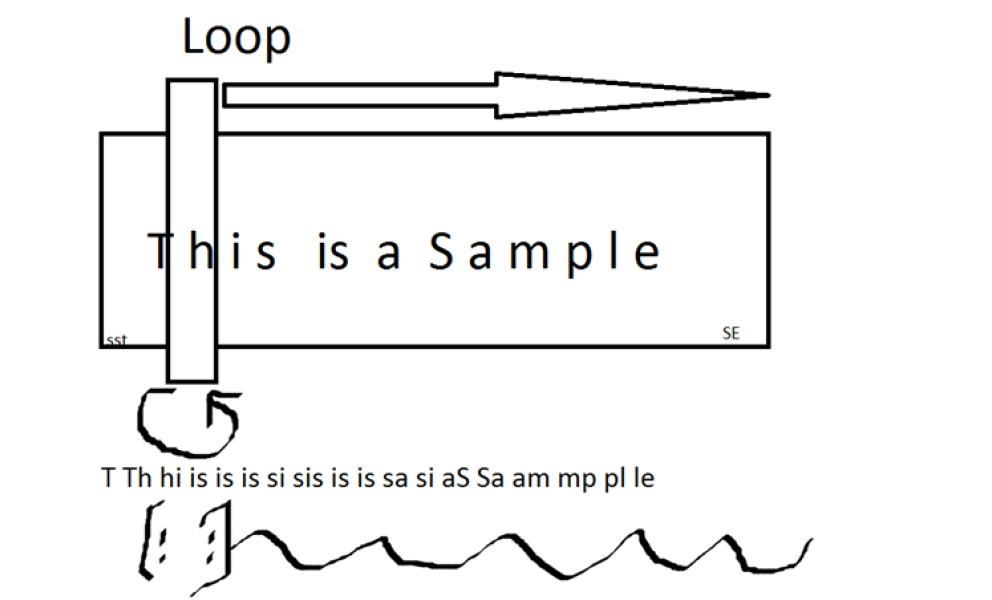

H) Differentiation through Rhythm

- Quantized loop: The loop length is a multiple of the sounding quantization unit of the sample: e.g. the sample contains sixteenth notes and the sample length is 7/16; this results in a perceptible beat.

- Non-quantized loop: The loop length is an irrational multiple of the time sequence within the loop; (vinyl loops) “damaged beats”.

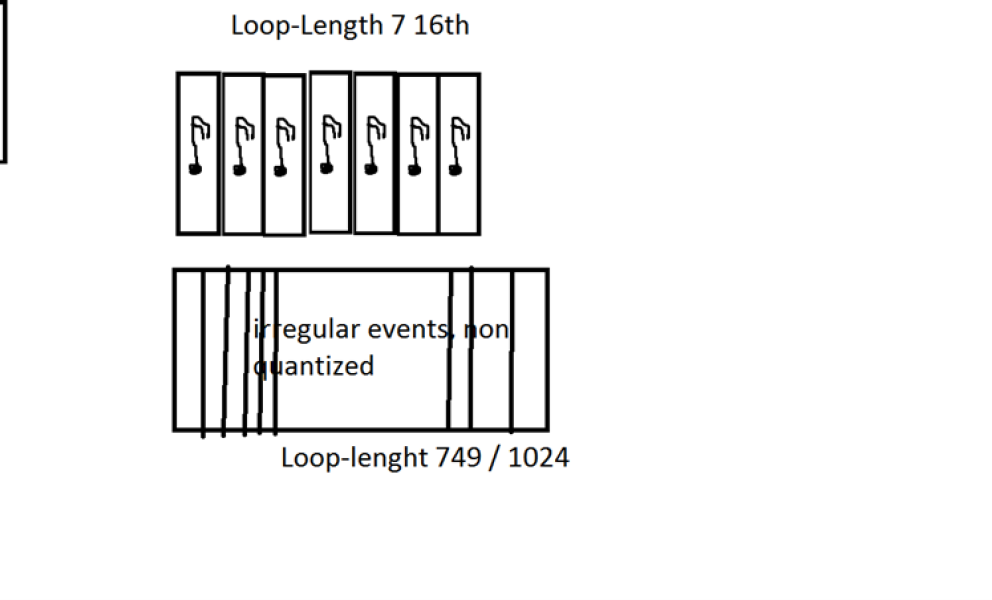

III. Grinding and time: the phenomenology of grinding time

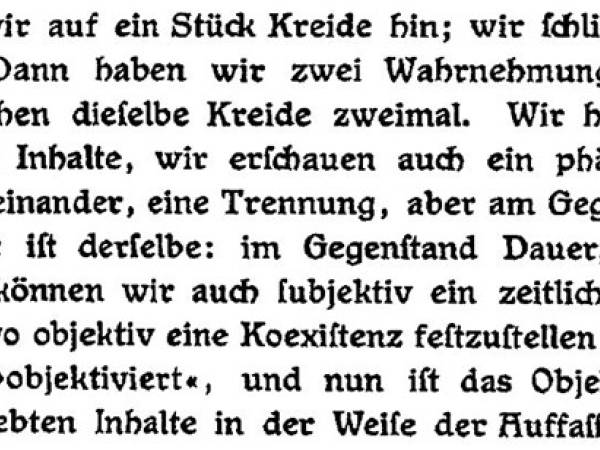

In his essay “On the Origin of Inner Time-Consciousness”, Edmund Husserl defines a concise phenomenology of time; it is based on the idea of a linearly progressive experience of time. However, this is already transcended by the concepts of prothension and retention, which include memory and moving forward and backward in time. Furthermore, he uses the sound of a single note as a paradigm for his discussion of the phenomenology of time.

“Duration of sensation and sensation of duration are two different things. And it is the same with succession. Succession of sensations and sensation of succession are not the same.”

It seems that the aforementioned inflection point in the temporal development of loops has a significant influence on our perception: it counteracts the linearly progressing experience of time and replaces it with something else.

The repetitions involved give us the impression of circularity rather than linearity, even though physical time is progressing in the meantime. We encounter a phenomenon that, despite all movement, we would describe as standstill rather than progress. (This does not apply to loops that already contain static information).

Altered experience of time corresponds to altered state of consciousness: loops can therefore be considered a means of altering consciousness.

If David Hume defines substance as repetition and habit, we might conclude that loops create a substance, similar to how the film image is created by repeated individual images. It is like creating a mirage based on vibration, but appearing as a static object.

Edmund Husserl: Logische Untersuchungen

Furthermore, the type-2 loops, the “short-term loops”, seem to correspond to the time span of short-term memory, which is also neurologically connected to the function of hypnosis. The hypnotic effect of many of Baumgärtel's loops could stem from this. William Burroughs explored this hypnosis function with his and Brian Gysin's Dream Machine, a rotating cylinder with a loop of patterns of flickering lights.

Nevertheless, as in the “backward” movement of Webern's crab melodies, the standstill and rewinding of time are illusions, subjective experiences with many consequences for aesthetics that arise from similar constructions.

Let's look at the time component of the different loop types systematically:

Granular Loops 50ms to 200m

In a granular loop, the content of the original disappears: and so does the original's timeline. Granular loops are used to create a time stretch, a multiplication of the original sample length.

Granular loops are used in granular synthesis to transform musical gestures into sound. (sound clouds); this application was mainly used in electronic music in the 1980s.

Short-term loops 200ms to 7000ms [“hypno loops”

These loops are mainly used in granular synthesis: it is a kind of time stretch, but with a different view of the content: a kind of microscopic analysis of the content, which is transformed and reinterpreted, revealing layers of meaning.

The best examples that illustrate the effect of these loops on our perception are by Raffael Montanez Ortiz.

“Our civilization sees the dream as irrational. I remember actually reading once about some scientist trying to invent a pill that would eliminate the toxin secreted by some gland in the brain that would then eliminate dreaming! We want to eliminate it, because we are a culture that is still suffering from nightmares, in contrast to the Senoi in Malaysia, where there is no nightmare, it's all been integrated by the time one gets through adolescence.

Then, your dreams serve your highest creative potential. The dream is for counsel, whether it's finding solutions for an illness, or ways to engineer a bridge that has to be built. So, the dream becomes the original art process, the art process that is inherent to our being, our imagining, our creativity. We daydream, we sleep dream. That imagining is the original art within which we make this bridge.” (Ortiz, Interview with Lauren Raine 1988.)

Ortiz uses digital image processing to initiate processes of de- and resemanticization. The film sequences of “Kiss” and “Conversation” refer not only to themselves as sign systems constructed by electronic means, but also to social processes. It is typical of Ortiz's method to dispense with social evaluations: instead of expressing a relationship to society, he creates occasions for reflection on processes that constitute socialization. The video shaman Ortiz transforms the mostly value-indifferent treatment of the film material of the video-Buddhist Nam June Paik into models of the “liminoid”. (Thomas Dreher)

Structural Loops 7000ms to max

“Whatever can be said about loops: the opposite is also true:” [The words of Hassan-I-Sabbah, Berlin 2016]

The functions of loops in their aesthetic consequences.

Loops as an instrument of a phenomenology of the gesture | Reinterpretation of the gestural, deconstruction of pathos | Theater of repetitions; Martin Arnold |

Loops as a sound magnifying glass | Husserl's table; the turning of an object | Morton Feldman |

Loops as a structure generator | Patterns and cells as a new musical atomistic/monadology | Ligeti, cellular automata |

Loops as an instrument of deconstruction | The different repetition/ irritative material illumination | Masquerade |

Loops as a generator of substance experience | Hume's concept of substance: constitution of the identical through repetition | |

Loops as an instrument of hypnosis/of self-oblivion | Burroughs, The Dream Machine Intoxication experience | DW2, Trance Music |

| Loops as a carrier of difference | Differente Wiederholungen, Zuck/Scratchrhytmen, Damage Beats Varianzen, die einen attraktiven Zustand umkreisen | Maskenspiel 1, Room full of Shoes Chop the Past |

Loops as a method of memorization | Bergson; Repetition as a form generator | Essay on forgetting |

Loops als Ausdruck/Resultat eines Automatismus | Loops in the process of automatic writing, automation of loops through digitized loops; the theme of the mechanical | Osman Spare, Dadaism |

Loops as a representation of cinematic structures (e.g. framerates) | The constitution of the image from the loops of differential single images. | |

Loops as an improvisation concept | Loops as a pre-compositional experimental procedure | VLO |

Loops as a non-linear, non-narrative principle | Breaking the linear narrative flow, William Burroughs' cut-up method |

- 1

Wenn sonst nichts klappt: Wiederholung wiederholen In Kunst, Popkultur, Film, Musik, Alltag, Theorie und Praxis. Mit Beiträgen u.a. von:

Katja Diefenbach, Juliane Rebentisch, Josephine Pryde, Eran Schaerf, Diedrich Diederichsen, Gunter Reski, Tabea Metzel, Stephan Dillemuth, Stephan Geene, Judith Hopf. https://www.sfkb.at/books/wenn-sonst-nichts-klappt-wiederholung-wiederholen/ - 2

Ein Manuskript oder ein Stück Schreibmaterial, auf dem spätere Schrift über ausgelöschte frühere Schrift gelegt wurde. Ursprung Mitte des 17. Jahrhunderts: über das Lateinische aus dem Griechischen palimpsēstos, von palin „wieder“ + psēstos „glatt gerieben“.

- 3

Aus: Schleifen, Zur Geschichte und Ästhetik des Loops, Kulturverlag Kadmos

- 4

§. 66. Dahero ein jedweder organischer Körper eines lebendigen Wesens eine Art von denen Göttlichen Machinen oder natürlichen automatibus ist / welche alle künstliche Automata unendlich übersteiget; allermaßen eine durch menschliche Kunst verfertigte Machine in allen ihren Teilen mechanisch ist. Zum Exempel: die Zähne an einem eisernen Rade haben gewisse Teile oder Stücke / welche in Ansehung unserer nicht weiter etwas künstliches sind / und nichts mehr in sich fassen / welches in Absicht auf den Gebrauch / worzu das Rad bestimmt ist / etwas mechanisches anzeiget. Alleine die Machinen der Natur / das ist / die lebendigen Körper sind auch unendlich fort gewisse Machinen in ihren geringsten Teilgen. Wodurch der Unterscheid / welcher zwischen der Natur und der Kunst / das ist / zwischen denen Göttlichen und Menschlichen Kunst-Werken ist / bestimmt wird.

§. 89. Gleichwie wir oben unter denen natürlichen Reichen / deren eines sich auf die causas efficientes, das andere auf die causas finales stützet / eine Harmonie dargetan haben; so müssen wir allhier auch eine andere Harmonie unter dem Physikalischen Reiche der Natur und unter dem moralischen Reiche der Gnade anmerken / das ist / in so weit Gott als ein Erbauer der ganzen Welt-Machine betrachtet / und in so weit er als ein Monarche der Göttlichen Stadt der Geister angesehen wird.

Daher ist jeder organische Körper eines Lebewesens eine Art göttliche Maschine oder natürlicher Automat, der alle künstlichen Automaten unendlich übertrifft. Denn eine Maschine, die durch die Geschicklichkeit des Menschen konstruiert wurde, ist nicht in jedem ihrer Teile eine Maschine; zum Beispiel haben die Zähne eines Messingrades Teile oder Stücke, die für uns keine künstlichen Produkte sind und nichts in sich enthalten, das den Verwendungszweck des Rades in der Maschine erkennen lässt. Die Maschinen der Natur, d. h. die lebenden Körper, sind jedoch bis ins kleinste Teilchen Maschinen. So groß ist der Unterschied zwischen Natur und Kunst, d. h. zwischen göttlicher und menschlicher Kunst.

Da wir oben festgestellt haben, dass es eine vollkommene Harmonie zwischen den beiden natürlichen Bereichen der effizienten und der Endursachen gibt, wird es hier angebracht sein, auf eine weitere Harmonie hinzuweisen, die zwischen dem physischen Bereich der Natur und dem moralischen Bereich der Gnade zu bestehen scheint, d. h. zwischen Gott, der als Architekt des Mechanismus der Welt betrachtet wird, und Gott, der als Monarch der göttlichen Stadt der Geister betrachtet wird.

Aus: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Monadologie

- 5

Erstmals wurde ich auf diese Möglichkeit durch ein Gepräch mit Peter Vuijca hingewiesen.

- 6

Für harmonische Strukturen habe ich die Harmonie der Differenz entwickelt, die durch virtuelle FM-Synthesizer realisiert wird.

- 7

Dies ist die absolute, positive Deterritorialisierung der abstrakten Maschine. Deshalb müssen Diagramme von Indizes, die territoriale Zeichen sind, aber auch von Ikonen, die zur Reterritorialisierung gehören, und von Symbolen, die zur relativen oder negativen Deterritorialisierung gehören, unterschieden werden. 41 Auf diese Weise diagrammatisch definiert, ist eine abstrakte Maschine weder eine Infrastruktur, die in letzter Instanz bestimmend ist noch eine transzendentale Idee, die in letzter Instanz bestimmend ist. Vielmehr spielt sie eine steuernde Rolle. Die diagrammatische oder abstrakte Maschine dient nicht dazu, etwas Reales darzustellen, sondern konstruiert vielmehr ein noch zu kommendes Reales, eine neue Art von Realität. Wenn sie also Schöpfungspunkte oder Potenzialitäten konstituiert, steht sie nicht außerhalb der Geschichte, sondern ist stattdessen immer „vor“ der Geschichte. Alles entkommt, alles erschafft – niemals allein, sondern durch eine abstrakte Maschine, die Intensitätskontinuen erzeugt, Deterritorialisierungsverbindungen bewirkt und Ausdrücke und Inhalte extrahiert. Dieses Real-Abstrakte ist völlig anders als die fiktive Abstraktion einer angeblich reinen Ausdrucksmaschine. Es ist ein Absolutes, aber eines, das weder undifferenziert noch transzendent ist. Abstrakte Maschinen haben also Eigennamen (sowie Daten), die natürlich keine Personen oder Subjekte bezeichnen, sondern Materien und Funktionen. Der Name eines Musikers oder Wissenschaftlers wird auf die gleiche Weise verwendet wie der Name eines Malers, der eine Farbe, eine Nuance, einen Ton oder eine Intensität bezeichnet: Es geht immer um eine Verbindung von Materie und Funktion. Die doppelte Deterritorialisierung von Stimme und Instrument wird durch eine abstrakte Wagner-Maschine, eine abstrakte Webern-Maschine usw. gekennzeichnet. In der Physik und Mathematik können wir von einer abstrakten Riemannschen Maschine sprechen, und in der Algebra von einer abstrakten Galoisschen Maschine (genau definiert durch eine beliebige Linie, die Hilfslinie genannt wird, die mit einem als Ausgangspunkt genommenen Körper konjugiert wird) usw. Es gibt ein Diagramm, wenn eine einzelne abstrakte Maschine direkt in einer Materie funktioniert.

G. Deleuze und F. Guattari

Bernhard Lang

Bernhard Lang, born in Linz in 1957, studied composition (with Andrzej Dobrowolski), piano, jazz theory and counterpoint at the Bruckner Conservatory and later at the University of Music and Performing Arts Graz. Additional studies in philosophy and German studies as well as composition courses with greats such as John Cage shaped his work. Active as an improvisational musician and jazz pianist, he turned to electronic music in 1985 and developed the CADMUS composition software. He founded the association "die andere saite" in 1987 and taught as an associate professor of composition in Graz from 2003. Lang has received numerous awards, including the Music Prize of the City of Vienna (2008) and the Austrian Art Prize (2019). His work includes music theater, orchestral and chamber music, electronic compositions, film music and music for dance and radio plays.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Bernhard Lang

Bernhard Lang

Bernhard Lang