13 Minuten

1. Introduction: Modes of Attention

There is a recurring suspicion in cultural theory that something essential has been lost in our modern modes of perception that have been induced by the current fragmented media environment. The terms “vertical” and “horizontal” perception have repeatedly been used to describe contrasting modes of attention. A “vertical” or deep mode of perception has been equated with introspective reflection and profound engagement with an artwork, whereas “horizontal” perception referred to scattered attention, an inability to focus on one thing at a time, and therefore the quasi-random collection of fragments.

Already long before the advent of social media, in his seminal critique of postmodernism (1991) Frederic Jameson famously contrasts the depth of Van Gogh’s Peasant Shoes with the “surface” of Warhol’s Diamond Dust Shoes – lamenting a collapse of meaning, a flattening of perspective, and a loss of verticality. In the domain of music, Marlies De Munck (2024) more recently echoes this concern. She describes a shift from the vertical listening of 19th-century absolute music – rooted in introspection and transcendence – to the horizontal listening first introduced by John Cage’s 4’33”, where attention drifts across surfaces and context replaces structure.

Both thinkers see this transformation as a form of diminishment. But what if the shift toward lateral attention – including today’s practices of browsing, skimming, sampling – is not a symptom of decline, but a new perceptual reality worth embracing?

Claire Bishop offers a more generous and, I believe, more productive take. In Disordered Attention (2024), she suggests that vertical and horizontal attention are not mutually exclusive, but dynamically intertwined. Our perception today doesn’t just skim – it moves between modes, accumulates meaning across time and context. Where Jameson and De Munck see fragmentation and a lack of profound perceptual engagement, Bishop sees potential and a departure from a normative idealization of one particular mode of attention.

This more generous understanding of attention brings up the question: what kinds of artistic forms are capable of working with – rather than against – our contemporary perceptual condition: the “vertical” AND the “horizontal”? One answer lies in the practice of transmedia composition.

2. Transmedia Composition

In transmedia composition, an art project encompasses several artworks, each using a distinct combination of media. It is an approach to composition that deliberately evokes various modes of perception. It operates across media, offering so-called “modes-of-encounter” of different qualities between the audience and the artwork – inviting both deep engagement and associative drift. Each individual part of a transmedia work can stand on its own, yet a fuller experience emerges only over time – through what I call “hermeneutic accrual”. Audiences navigate across formats, contexts, and sensory environments, layering perspectives as they go.

This way of working across media to construct meaning is not new. In fact, it might be as old as human culture. Throughout history, cultures have turned to multiple forms of expression to communicate complex ideas. Religions, for example, articulate what we might now recognize as an “idea-scape”, through texts, but also ritualistic practices, architecture, symbols, music, painting, and more. Each element may function independently, but together they build a network of meaning. Importantly, no single medium holds the entire message; meaning emerges through how these media interact across time, space, and experience.

In a more contemporary context, the Austrian composer Peter Ablinger offers a striking example of this principle. His project Weiss/Weisslich started in 1980 with the most recent work being completed in 2023. It spans a vast range of media: from rustling trees (Nr. 26) and city noise (Nr. 5) to graphs (Nr. 7c) or photos (Nr. 11), installations (Nr. 7 and many more), and found sound-producing objects (Nr. 8). Each piece is autonomous, yet all are connected through a shared conceptual lens: the exploration of noise and perception, and the association of noise with the color white. They do not build a narrative in the conventional sense, but they cohere through an evolving idea-scape. A listener who encounters one piece in a gallery and another years later in a concert hall may still intuitively relate them to one another and piece together a larger, conceptual structure and an evolving understanding of the projects focal point.

In a different context, Björk’s Biophilia (2011) exemplifies transmedia composition in a popular music context. What was first released as an album in different artfully designed editions, expanded into a series of interactive apps, live performances, educational workshops, installations, and even a documentary. Each component offered a different mode-of-encounter, yet all circled around a core thematic constellation: the relation between nature, culture and science. Here, too, the full scope of the work only emerges over time, across media.

Transmedia composition, then, is not simply about using multiple media in a single work, as in multimedia or intermedia. It is about building a network of works, each autonomous but conceptually intertwined, and about engaging audiences through different perceptual and interpretive pathways. It rethinks composition not as a singular and linear act of authorship but as a distributed, evolving process – one that mirrors how we increasingly consume, interpret, and construct meaning in a complex media landscape.

3. Key Criteria: Idea-Scapes, Modes-of-Encounter, Hermeneutic Accrual

In order to describe key characteristics of transmedia projects, I would like to discuss three terms, which I have already mentioned in passing: Idea-Scape, Modes-of-Encounter, and Hermeneutic Accrual.

3.1 Idea-Scape

An idea-scape is the thematic or conceptual common denominator that is shared by all works that belong to a transmedia composition. It is the shared space of inquiry – which can be very abstract, or a concrete narrative – that connects otherwise distinct works. Borrowing from terms like landscape and soundscape, idea-scape emphasizes continuity, and the interplay of top-down and bottom-up design processes. Think of it as a field of gravity: different pieces orbit within it, each offering a unique vantage point, but all responding to the same pull.

3.2 Mode-of-Encounter

We often speak about what a work of art is, but less frequently about how we come into contact with it. Yet this “how” – the conditions of engagement, the spatial and sensory framing, the audience’s physical and cognitive positioning – is often just as important in shaping how we make sense of a work. I use the term modes-of-encounter to describe this aspect: the interplay of media, environment, and perceptual cues that shape how an audience meets an artwork.

Some works ask us to sit in silence in a darkened hall. Others invite us to move, interact, scroll, touch, speak. Some unfold through headphones in intimate proximity; others through multi-sensory installations in expansive spaces. Each of these settings carries its own codes, expectations, and affective textures, and each reshapes the meaning of the work it presents.

In transmedia composition, designing distinct modes-of-encounter is part of the composition: The spatial layout, the sensory modality (audio/visual/tactile), the affordances of interaction – all of these define the mode-of-encounter, and by extension, the interpretive possibilities.

3.3 Hermeneutic Accrual

Because the parts of a transmedia composition are autonomous and presented at different times and places, audiences may encounter them in any order, and at different times. Understanding unfolds cumulatively, not linearly—a process I call hermeneutic accrual. While each individual work may suggest more “vertical” or “horizontal” attention, depending on the mode-of-encounter it proposes, the cumulative process inherently invites horizontal perception. The “space” where the different works come together is the audience’s memory – this is where they gain a so-called “asynchronous presence” (Ciciliani 2021) – asynchronous, as they have been experienced at different times. The short-term memory activated in the moment of encounter interacts with long-term memory, where filtered impressions of earlier works are stored. Each new encounter sheds light on the others, adding layers of nuance, resonance, or contradiction. Interpretation becomes dynamic: vertical (deep, reflective) and horizontal (relational, networked) attention interact to construct meaning.

A Case in Point: Why Frets?

My own project Why Frets? illustrates how these concepts operate in practice. Structured around a fictional history of the electric guitar told from the vantage point of 2083, the project comprises three principal distinct components: a multimedia concert (Why Frets? - Downtown 1983), an installation (Why Frets? - Tombstone), a lecture-performance (Why Frets? - Requiem for the Electric Guitar). The publication of the project in the form of a book (Why Frets? 2083) with an integrated USB stick further extends the project and can be considered a fourth part. A fifth part is an online experience accessible via QR code (Why Frets? - Necromancy).

LINK: Why Frets? 2083 https://www.galerie-der-abseitigen-kuenste.de/publikation/why-frets

Each part can be experienced independently. The concert immerses listeners in a performative present, the lecture-performance starts as a pseudo-historical academic lecture that grows increasingly absurd, the installation allows for open-ended interactive exploration. But together, they form a web of references—an idea-scape about fiction, gender roles, music history, and cultural fetishization. The audience may encounter one part live, another in a book, another years later online.

Each mode-of-encounter invites a different kind of engagement: passive listening, active reading, spatial exploration. And across these, the interplay between vertical and horizontal perception unfolds. At one moment, deep attention is rewarded; at another, it’s lateral comparison that unlocks a new insight.

4. Towards Analysis: Differentiating Models of Transmedia

So far, I have focused on how transmedia composition unfolds over time and across different perceptual settings, with concepts like idea-scapes, modes-of-encounter, and hermeneutic accrual describing key characteristics. But to deepen our understanding it is helpful to differentiate how content travels across media. Or in other words: how does an idea-scape sediment in the individual parts of a transmedia project and what kinds of relationships are created between those parts?

To this end, I have developed a typology of transmedia models. It is based on narratological theory—particularly Marie-Laure Ryan’s (2022: 184–185) categories of transmedia storytelling—but adapted and expanded to suit the needs of music-based transmedia composition. These models are not meant to be strict categories, but lenses through which we can understand and compare different approaches.

Let me briefly introduce three core models I have found useful so far: Expansion, Translation, and Segregation.

4.1 Expansion

In this model, different parts of a transmedia project contribute complementary perspectives to a shared idea-scape. Each component adds content or context that is not found in the others, creating a multi-faceted view of the central concept. The relationship here is additive. There might be overlaps in the sense that particular motifs reappear in different parts, but what dominates is that each part adds new content or unique perspectives.

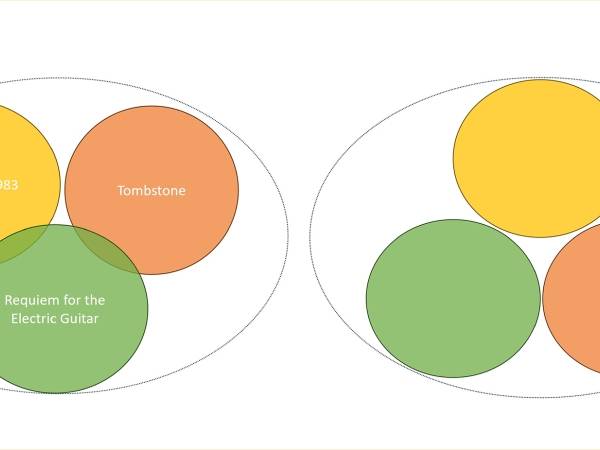

My project Why Frets? is a good example. Individual elements from the performance-lecture Why Frets? – Requiem for the Electric Guitar can be found on both of the other main parts, however, there is no overlap between Why Frets? – Downtown 1983 and Why Frets? – Tombstone, as illustrated in Fig.1. A constellation with no overlaps at all would also be conceivable, see Fig. 2. In both illustrations the dotted ellipse designates the shared idea-scape.

Fig.1 and 2: left: the relationships between the three main parts of Why Frets?. There are overlaps in content between Requiem and the other two, however, Downtown and Tombstone do not share any material. Right: an arrangement would be conceivable with no overlaps at all. The dotted circle designates the idea-scape which is shared by all elements.

4.2 Translation

Translation involves recontextualizing material across media in a way that changes how it is perceived. Unlike Expansion, which introduces new content, Translation is about reinterpreting the same idea – or even the same material – through a different medium.

Translation highlights medium-specific differences and invites audiences to compare the form of engagement, not just the content.

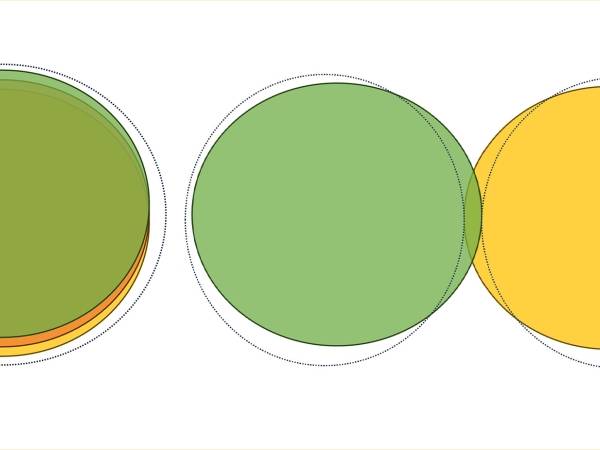

In my own project Pop Wall Alphabet, for instance – where sounds, images, and texts are derived from the same conceptual base –, provide unique aesthetic engagements, largely as a result of the unique affordances and specificities of each medium. When represented graphically, this would result in complete overlaps of the spheres that are designating the individual parts (Fig.3).

LINK: https://www.ciciliani.com/pwa.html

However, a complete recontextualization can also lead to the formation of different idea-scapes. James Joyce’s Ulysses for example reimagines Homer’s Odyssey, situating its themes in a radically different cultural and temporal context (Fig. 4). While the existence of a homogenous idea-scape is usually considered to be the foundation of every transmedia project (Ryan 2022) the substantial alteration of contexts in transmedia translations often leads to different idea-scapes, within which only a single key element of the content remains constant – Odysseus’ storyworld is a fundamentally different one than the one by Leopold Bloom (Fig.4, Thon 2018: 378ff).

Fig.3 and 4: left: maximum overlap between all parts as in Pop Wall Alphabet (2015). Here the medium specificities of text, image, and sound lead to strong qualitative differences between the individual parts. Right: two narratives share a key element, but the fundamental change of the context leads to the formation of two separate idea-scapes.

4.3 Segregation

In segregation, a single element is removed from its original context and presented on its own. The content does not change – it is the framing that does. And yet, this reframing can radically alter the experience and interpretation of the work.

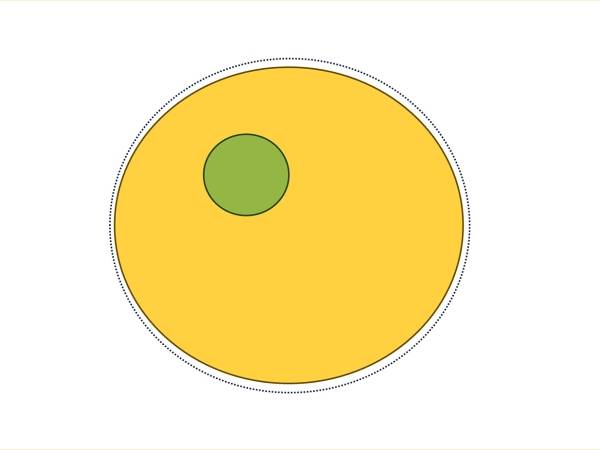

Thorolf Thuestad’s For one – for many – for all (2021) exemplifies this approach, with kinetic objects presented in both as a central element in a theatrical performance, and – in isolation – as a gallery exhibition (Fig. 5).

Segregation shares similarities with transformation – both involve the change of context that leads to a qualitative shift. In contrast to transformation, in segregation the change of context occurs through reduction or isolation.

Fig. 5: Segregation, isolates an element and presents it as an artwork in itself.

These models are tools, not rules. A given project may move between them—or combine all three. But by naming them, it helps me to think more clearly about the compositional choices involved in transmedia work and as this research evolves, I hope to discover and develop additional models.

These models also point to how transmedia composition is not only about creating discrete works across media, but about designing relationships that invite vertical reflection, horizontal connection, or moments of dissonance and surprise.

5. Outlook and Sociopolitical Resonance

The models outlined above invite further experimentation: What happens if we push these structures to their limits? Can a transmedia composition for example include elements so different in scale or form that they barely seem to belong together – say, a single haiku in one part and a durational, six-hour performance in another?

If each part of a transmedia project offers a unique perspective on a central theme – or idea-scape – how strongly can they diverge before the sense of cohesion begins to falter? In other words: How far can you stretch the boundaries of the idea-scape before its internal coherence dissolves? And what happens if it does? Is there a productive threshold where coherence begins to blur, yet a deeper kind of resonance emerges – not from clarity, but from tension, contrast, or even contradiction?

Even the idea of translation, when applied beyond literature, raises intriguing questions. Joyce’s Ulysses may transform the Odyssey, but what would a musical or visual transmedia equivalent look like? Can a single element provide a stable point of reference around which a multitude of contrasting idea-scapes unfold?

Naming the discussed standard models helps me to imagine such challenging approaches that raise interesting artistic questions that can only be explored in creative practice. These frameworks not only guide artistic inquiry; they offer a space for testing how meaning is constructed in complex, multi-modal environments. What is at stake is not merely innovation for its own sake, but a rethinking of how meaning is made, shared, and experienced in a world saturated with overlapping media and fractured attention.

Transmedia composition does not demand that audiences consume everything, nor that they arrive at a single reading. Instead, it invites them into a process of assembling meaning – one that mirrors the fragmented, multi-perspective way we now experience the world.

In this sense, transmedia composition is not only a compositional method; it is a sociopolitical gesture. As mentioned earlier, transmedia – that is the practice of spreading meaning across different media – is not new. On the contrary: For as long as humans have expressed meaning – through ritual, storytelling, architecture, music, and image – we have done so across media.

But today, in a culture shaped by fragmentation, saturation, and disordered attention, transmedia composition gains new relevance. It resonates with how we already move through information, perception, and narrative, and offers a more deliberate, critical, and imaginative way of doing so. That is why it deserves to be explored more deeply, both artistically and theoretically. Not as a novelty, but as a practice that has always been with us and whose time, perhaps more than ever, has come.

Marko Ciciliani

Marko Ciciliani is a composer, intermedia artist, performer and artistic researcher, as well as Professor for Computer Music Composition at the Kunstuni Graz. The focus of his work lies in the composition of performative electronic sound works, mostly in audiovisual contexts. Interactive video, light design and laser graphics often play an integral part in his works, just as well as elements of ergodic or transmedia storytelling, or speculative fabulation. His music has been performed in more than forty-five countries across Eurasia, Oceania and the Americas. His work has been released on five full-length CDs and four multimedia books featuring inter- and transdisciplinary works.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Marko Ciciliani

Marko Ciciliani

Marko Ciciliani